Through The Hamidiya Knights

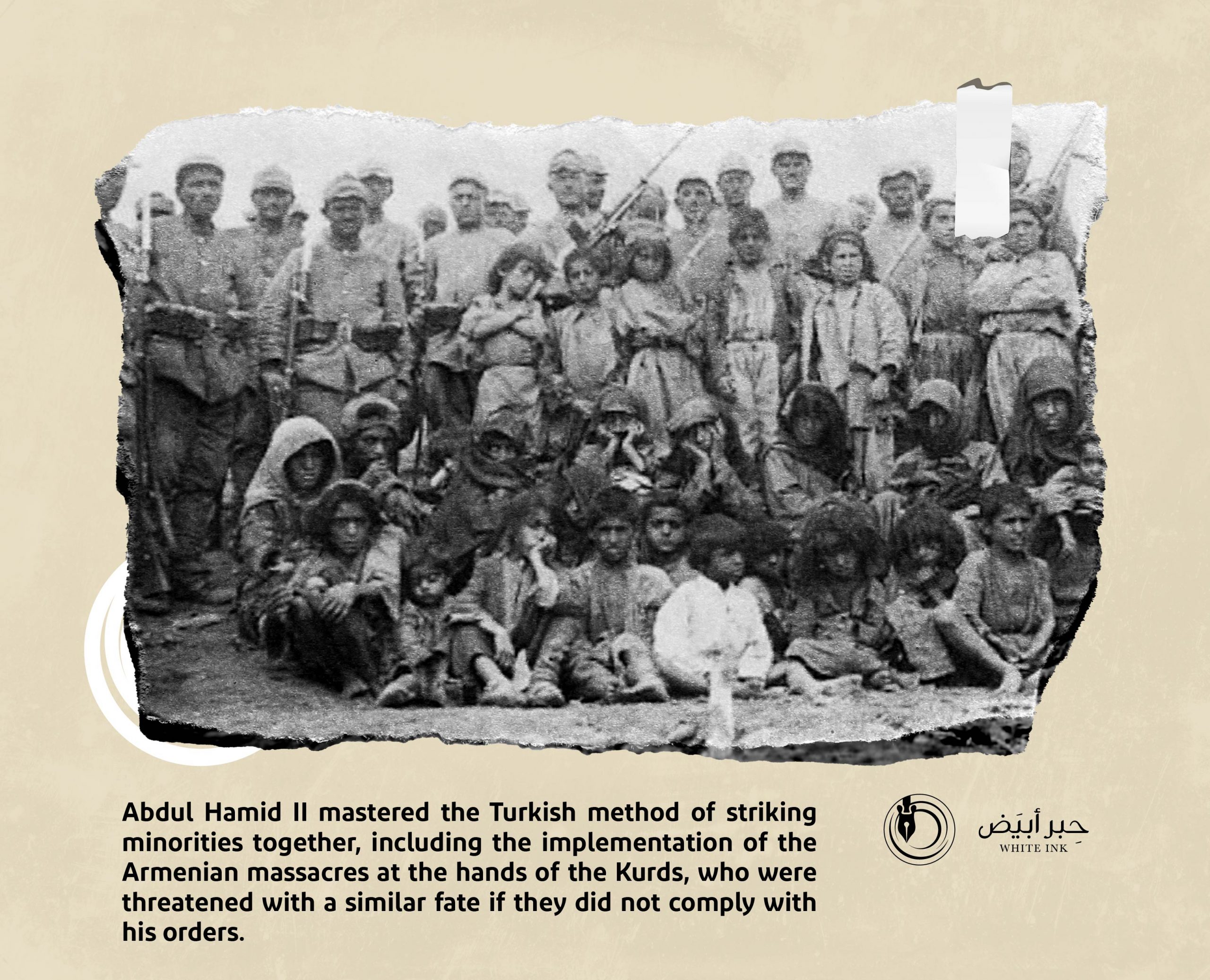

The Red Sultan used the Kurds to kill the Armenians and the Assyrians

As the Ottomans always do, they use mercenaries and foreign fighters, Abdul Hamid II established one of the bloodiest Ottoman military divisions, a purely Kurdish division, when he took advantage of the Kurds’ submission to the Ottoman occupation, and began converting part of them to serve his tyrannical project and save his state, which was at risk to fall.

Abdul Hamid’s state was groaning under the weight of decline, collapse and slow death when some Kurds agreed to engage in the Ottoman project after major massacres were committed against them by the Ottomans like other minorities, since whoever opposes the policy of Abdul Hamid II or refuses to work within his project, his fate is murder and torture. As the Ottomans did with the Armenians and Arabs, hundreds of thousands of whom were killed and displaced, only because some of them refused to fight with the Ottoman army against their opponents.

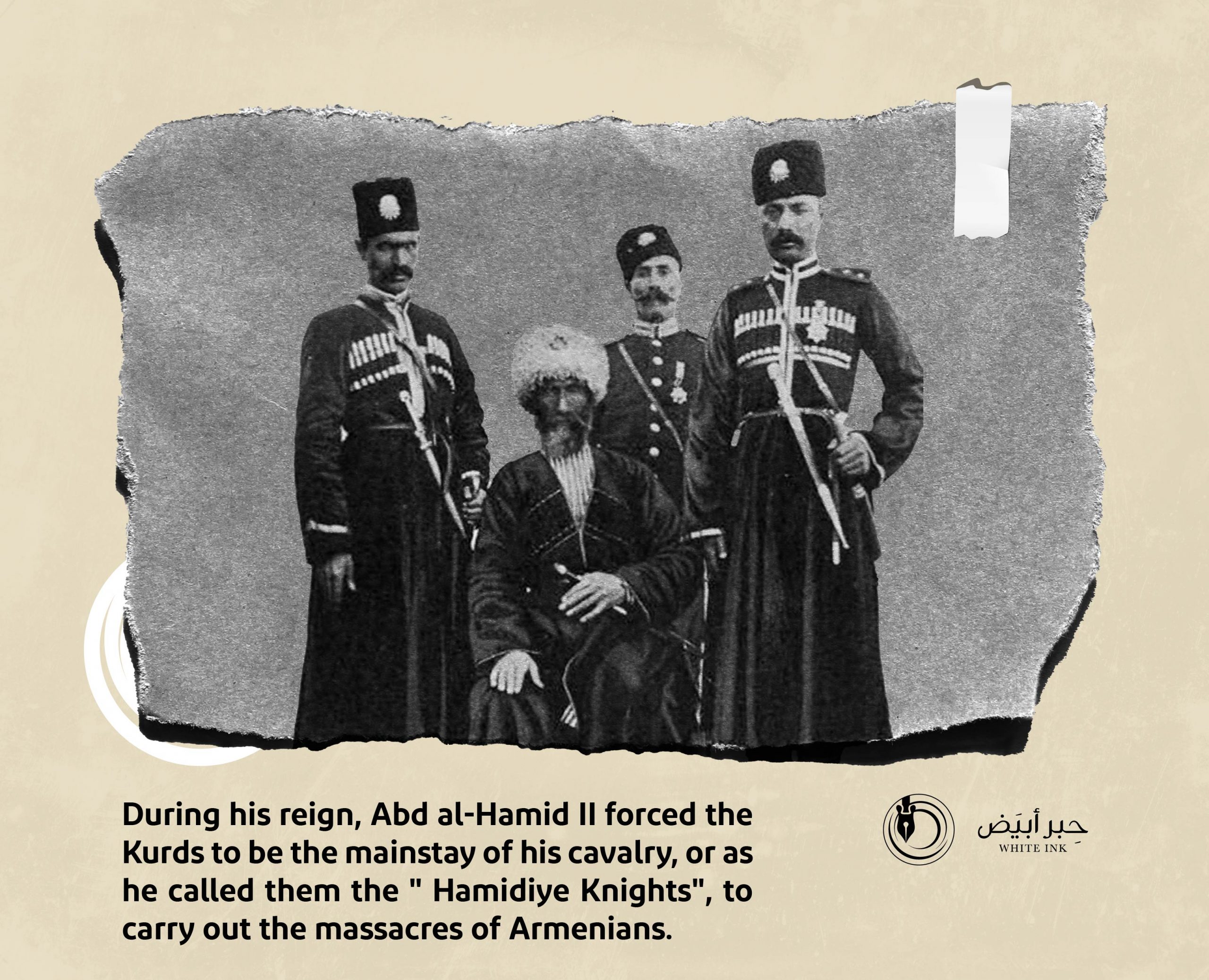

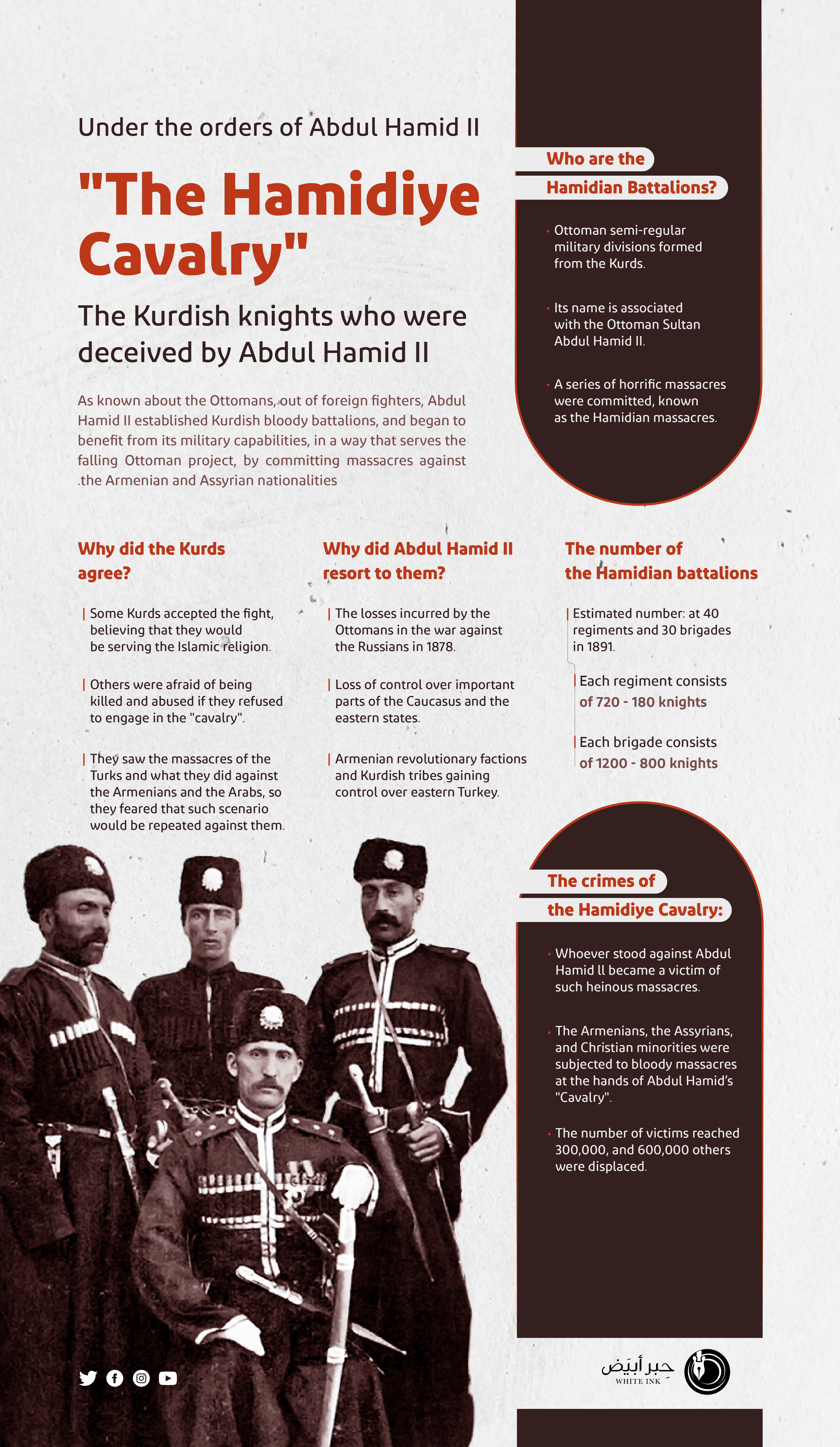

The Jordanian writer Khaled Bashir refers – in his post – to the “Hafriyat” blog that the Hamidiya Battalions, or the Hamidiya cavalry, were semi-regular Ottoman military divisions, formed from Kurdish fighting knights; their name was associated with the Ottoman Abdul Hamid II, who was the founder and sponsor. Soon enough, it was a reason why the Sultan’s name was also associated with a series of horrific massacres, known as the ” Hamidiya massacres”.

The ferocious massacres committed by the Ottomans against the Armenians and the Arabs forced the Kurds agree to join the Turkish death squads.

The Russian-Ottoman war ended in (1878 AD) with the defeat of the Ottomans and they lost significant parts of the Caucasus region, while the eastern states remained free from the actual control of the Ottoman armies, which were exhausted and depleted by the war, leaving room for control by multiple local parties, such as Kurdish tribes, and the Armenian revolutionary groups that had begun to emerge and become active during that period among the Armenian villages and cities in the east of the Ottoman Empire. Perhaps the most prominent motives of Abdul Hamid II to resort to minorities to protect his throne are the grave dangers that hovered around his state, the disintegration of his army, and the erosion of trust in his ability to confront these upcoming dangers, especially after the successive defeats his army suffered.

The documents of the Kurdish clans say: The founder of the idea of the Knights is the Commander-in-Chief of the Ottoman forces, Shakir Pasha, and the reason behind the establishment of the Hamidiya Knights is to facilitate the control of the Kurds. On the other hand, the Russians believed that the Hamidiya Knights had been formed with a British recommendation to stand against the Russians, and they suggested to the Ottomans that Zaki Pasha, the commander of the fourth army, be responsible for its formation, and the Ottoman Sultanate at the time was afraid of the repetition of Kurdish alliances, such as the holy alliance established by Badrakhan Pasha in the fourth decade of the nineteenth century, and the League of Kurds established by Sheikh Obaidullah Al-Nahri in the eighties of the same century, in which more than 200 Kurdish clan chief and influential participated. For these reasons, Turkish officials in the capital eventually considered forming the Hamidiya Knights.

In the attempt of establishing the Hamidiya Battalions, Abdul Hamid II benefited from the Russians, who conducted a similar experiment by forming a force of Kurdish fighters living behind the Caucasus, so he formed two Kurdish regiments under the command of Colonel Loris Milikov, whose name was known as “The Cossacks” in (1878), and that force formed by the Russians for military operations. Nayef Karkari says in his publication about the story of the emergence of the Hamidiya divisions: “The motive for establishing the Hamidiya Knights was that the Ottomans were in constant conflict with the Russians, and they wanted to take advantage of the strength of the Kurdish fighter known for his courage and fighting ability, and to protect the Ottoman lands from British incursion in Anatolia. This is on the external level, as for the internal level, the goal was to get a hold on the Kurdish clans, especially the feudal clans – loyal to the Ottomans – and to extend their influence over Kurdistan in general, so that the clans would surrender to them and be under the control of the Ottoman Empire.

Abdul Hamid II got the idea of the death squads from the Russians who recruited the Kurds behind the Caucasus in the Crimean Wars in 1853.

On the other hand, the goals of the Kurdish clans towards joining the formation of the Hamidiya Knights, varied; some of them wanted to form an armed force of their own men to protect the clan and to strengthen its clan influence, and some saw the appropriate opportunity to regain the power that it had previously lost, and there are those who entered into those formations to evade soldiering and military service.

In (1891 AD), the number of the Hamidiya regiments was estimated at 40. Later, it increased until it reached 30 brigades, and the regiment consisted of 180 knights, as a minimum, and up to 720 knights, as a maximum. As for the brigade, it consisted of 800 knights, as a minimum, and 1200 knights, as a maximum.

These regiments and brigades committed massacres with the arrangement, approval and planning of Abdul Hamid II. The Ottomans wanted to commit heinous massacres, but they never wanted to be accused, so the idea of the Kurdish regiments delivered a satisfactory solution for one of them to carry out bad deeds, such as confronting the Armenian movement that wanted to get rid of the odious Ottoman occupation, and it engulfed a large number of villages and cities in eastern Anatolia, and due to the unwillingness to show that the suppression of the Armenian revolution came by the regular Ottoman army, and the rejection and condemnation of the European International that this brings, it was decided to rely on the Hamidiya battalions to carry out the task of subjugating and suppressing the Armenian revolutionaries, so the result was: The Hamidiya massacres.

The results of the Hamidiya Knights Battalions were terrifying, following heinous massacres committed against everyone who stood in the way of the Ottomans and the authority of Abdul Hamid, whether they were Armenians or Assyrians and other Christian minorities, accompanied by displacements, demolitions and burning of houses and churches. While the total victims of the Hamidiya massacres in less than two years, according to the documents of the European consulates in the Ottoman Empire, were about 300,000 victims, in addition to the forced deportation of nearly 600,000 Armenians and Assyrians towards the southern regions of the Ottoman Empire. A series of sporadic killings, especially against the Assyrians, continued until 1900.

The Hamidiya Knights Battalions, which was sponsored by Abdul Hamid II, were famous for their unprecedented bloodshed and atrocities in wars, and the reason for such reliance on this type of irregular regiments known for not being bound by any boundaries or restrictions in wars and confrontations and such regiments are not subject to any standards or boundaries that regular military institutions are subject to. In addition to the emotional charge caused by anti-Armenian and Assyrian propaganda, which filled the Kurds’ feelings with anger against other minorities, considering that other nationalities are traitors and agents, as described by the Ottomans.

- Ali Hswn, The Ottomans and the Russians (Beirut: Islam House, 1982).

- Muhammad Al-Alawi and Ban Al-Ghanim, The Armenian Issue and the West stand towards it during the Reign of the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hameed II, Basic Education College Research Magazine at the University of Babylon, V (12), p.1, (2012).

- Mishaal Zahir, Armenians during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II 1876-1908, Journal of Basrah University.

- Majid Muhammad Yunus Zakhoy, Al-Hamidiya, a historical and analytical study, Council of the College of Arts, University of Mosul, (2006).

- Khaled Bashir, What do you know about the Ottoman “Hamidiya Battalions”?, Hafriyat website.

- Nayef Karaki, Al-Kharangiya from the Hamidiya Knights to the Tails of the Republic… The Story of Betrayal, Baznews

Obaidullah al-Nahri's revolution was their dream of independence

The Ottomans allied with the Persians to thwart the Kurdish dream

During the nineteenth century, the Ottoman Empire suffered from political, economic and military crises, and all attempts to reform the situation failed, and those crises increased after the Crimean War (1854-1856) and the Russo-Ottoman War (1887-1878), which contributed to the further deterioration of the economic conditions until the state got to the brink of bankruptcy. This affected most of its various states and territories, including the land of Kurdistan, which previously suffered from the unjust policies of the Ottoman, and from the misconduct of Ottoman officials, in addition to the marginalization, neglection, the imposition of various taxes and compulsory recruitment to the natives.

The situation of the Kurds worsened after the Ottoman Empire grew weaker subsequent to the Crimean War.

All of these factors combined together affected the economic life of the Kurds and their system based on agriculture and grazing. The situation got worse and desperate; famine spread, followed by the spread of epidemics and diseases.

The nature of the Kurds and their life were not separated from their lands and their deep and powerful links with it, as it is what provides them and their livestock with sustenance by farming and grazing them. That nature made the Kurdish element imbued with the love of the land and closely related to it.

These factors and the miserable conditions the Kurds lived through, were the reason why the Kurds changed their view of the Ottoman Empire, so they took a negative, rather extreme and often hostile stance. This was evident in the repeated rebellions and revolutions against the Ottoman empire, as Kurdistan witnessed many revolutions against the Ottomans, especially after (1820), such as the revolution of the Zazas, followed – in the period between (1829-1839) – the revolutions of Hakkari, Rawanduz, Tur Abdin, and the revolution of Sharif Khan Badlisi; however, all of these revolutions failed and resulted in the fall of most of the Kurdish emirates until, in 1847, they languished under the tyrannical Ottoman rule.

Poverty, poor living conditions, taxes, and compulsory recruitment made the Kurds detest the Ottomans.

The Kurdish revolutions increased; thus, the antagonism toward the Ottoman state was aggravated, subsequent to Kurdistan directly submitted to rule of the Ottomans. Most of those revolutions in their infancy, aimed at independence and achieving the principle of preserving the land and its bounties. Then, that principle developed into the idea of autonomy within the motherland. The goal of the Kurds was to achieve independence in decision-making and self-rule, through the ideas of Kurdish tribal leaders. At the end of the nineteenth century, they tried to reduce reliance on tribal leaders in order to reach the idea of nationalism; at that time, a new approach was formed that rooted the values and ideology of Kurdish nationalism. Then, the widespread popular uprisings led by Sheikh Obaidullah bin Taha Al-Nahri, took-place in the year 1880; he is one of the sheikhs of the Sufi orders with wide influence, spread and pervasive throughout Kurdistan; his revolution is one of the most important and last revolutions, as the revolution broke out in the Iranian lands adjacent to the city of Shamdinan in the Gulmerek region, and he was able to extend his control in many areas, he even managed to take control of many Kurdish regions, and he owned a lot of land, in addition to 200 villages that he obtained from the Ottoman authorities, and the other part he inherited from his father, Sheikh Taha. This made him widely influential until he became one of the best Kurdish leaders, as he is a descendant of the famous Kurdish Shamdinan family, which was highly respected among the people of the region.

A number of historians have attributed the most important reasons for the outbreak of the revolution of Sheikh Obaidullah al-Nahri, to the deteriorating economic conditions in all Kurdish regions, which was one of the most important causes of the revolution, and the unjust and inequitable policy used by the Ottoman and Iranian states in the Kurdish regions; all of this made Obaidullah willing to protect his Kurdish nationalism, and a reason for uniting the Kurds in an independent state, and this idea took over his mind.

The revolution broke out in October (1880) and was led by Sheikh Obaidullah al-Nahri, in the Chemdinan region, affiliated to Hakkari state, south of Van state on the Ottoman-Iranian border in northern Kurdistan, in which most of the Kurdish tribes participated. The revolution lasted for two months, during which, the leader was unable to achieve the goals he sought and set his sights on, which is the unification of the two parts of Kurdistan, the Ottoman and the Iranian, and the establishment of a Kurdish national state under his leadership. However, the joint military intervention of the Ottoman and Iranian states put an end to the activity of that revolution and its leader, as Al-Nahri returned to Chemdinan; from there he was sent to Istanbul. He soon managed to escape from the capital and returned to Chemdinan through the Caucasus Road, and was arrested again and exiled to Makkah, and died there in (1883). With his death, the dream of Kurdish independence was put to end. It is enough that Obaidullah stood against injustice in both countries, and it is also credited to him, that he was the first to establish the idea of a Kurdish national state.

- Ibrahim Al-Daqouqi, Turkey’s Kurds, 2nd Edition (Erbil: Aras Publications, 2008).

- Ahmed Taj Aldin, Kurdish history of the people and the cause of the homeland (Cairo: Dar-Althakafia for Publishing, 2001).

- Basile Nikitin: Kurds sociological and historical study, translated by: Nouri Talabani, 2nd Edition (Beirut: Dar Al-Saqi, 2001).

- Saadi Othman Hruti, Kurdistan and the Ottoman Empire: A Study of the Influence of Ottoman Domination Policy (Erbil: Mokiriani Foundation for Research and Publishing, 2008).

- Kazem Haidar, The Kurds: from where and to where (Beirut: Dar Alfekr Alhor, 1959).

- Mohib Allah, The Location of the Kurds and Kurdistan, Historically, Geographically and Culturally (without a publisher.: without a publishing house, 1991).

- Hwkr Tahir Tawfiq, Kurds and the issue of the Armenian (Beirut: Dar Alfarabi, 2014).

After World War I

Atatürk repeated Selim's I scenario to deceive the Kurdish people

Most of the Kurds lived within the states of the Ottoman Empire, and a part of them lived outside the borders of the Ottomans under political regimes; most of them were in Iran. According to the Ottoman statistics, some Turkish references estimate the number of Kurds within the Ottoman states in 1844 at about one million out of a total of 35 million inhabitants of the Ottoman Empire in its various states.

The Kurds played an important role throughout the Ottoman history, started with the alliance of the Kurdish Emirates with Selim I against Shah Ismail al-Safavi. Subsequently, the Ottomans bared their teeth when they exploited the Kurdish Nationalism for their benefit, and tried to domesticate and fuse it into the Turkish culture, which led to a direct clash between the Kurdish emirates and the Ottoman army; accordingly, the Kurdish Emirates lost their independence, which they enjoyed starting from the borders of the Ottomans, and were directly subjected to Istanbul. At that time, pages of hostility and clash between the Kurds and the Turks began.

Another new page in the history of Kurdish-Turkish relations, which began with the end of World War I and the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, as the allied forces began to invade the states of the Ottoman Empire and even the heart of the state – Istanbul – and it became as if these Allied forces intended to divide the Turkish lands among themselves. To top it all off, the Ottoman government in Istanbul accepted the Treaty of Sèvres concluded on August 10 (1920), which was not in favor of the Turks. At this point, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk came through, as he succeeded in forming a national government in Anatolia, and was able to gather the remainder of the Ottoman army under his control, as Atatürk rejected the Treaty of Sèvres, and was determined to resist the Allied forces that invaded the Turkish lands.

The Kurds fought alongside the Turks in World War I, and their favor was returned with repression, marginalization and executions.

As Sultan Selim I did when he asked to form an alliance with the Kurds during his conflict with the Safavids, Atatürk asked for help and sought for an allyiance with the Kurds to stand up to the Christian European invasion, and to support Islam and the Caliphate. Atatürk gave his word to the Kurds, that he would achieve their ambitions if they would stand by him against the invaders until achieving victory. Most of the Kurdish leaders already agreed to ally with Atatürk against the foreign armies, and their motive was to believe Atatürk, and in retaliation for the English army that occupied southern Kurdistan – i.e., Iraqi Kurdistan – as Iraq was occupied by Britain in World War I.

Kurdish sources mention that Atatürk told the Kurdish leaders that the Turks and the Kurds are the original owners of the country, and that victory will come by their hands, and that after achieving victory, Atatürk will recognize the independence of Kurdistan, and that the rights he will grant them shall be much more than what was stipulated in the Treaty of Sèvres, which Atatürk did not recognize.

Therefore, the Kurds joined the Turkish army led by Atatürk. The increase in the number of Kurdish people’s representatives in the National Council formed by Atatürk in Ankara after the fall of Istanbul to the Allied forces, helped with that. Meanwhile, the Peace Conference in Paris was looking into the conditions of the Ottoman states and the peoples subject to them. A representative of the Kurdish people in this conference was the Kurdish General, Sharif Pasha, who was the head of the Kurdish delegation to the conference. The Kurds’ support to Atatürk and the Turkish army in Anatolia, turned the scales; as the allies realized that the Kurds were not on their side.

According to Turkish sources, Kemal Atatürk managed to win over the Kurdish representatives to his side, and even sent the representative of the Kurds in the Lausanne conference, Ismat Pasha the Kurdish, to the conference that took place after the failure of the Treaty of Sèvres, where the latter was – at the same time – a representative of Turkey. At that time, he stated the famous historical declaration: “Turkey is for the Turkish and Kurdish peoples, who are equal before the Empire and enjoy equal national rights.” This led the members of the Lausanne Conference to abandon the idea of the independence of Kurdistan, and to accept the idea of Turkey as a state with two peoples: Turkish and Kurdish. Thus, the Treaty of Lausanne failed to address the national rights and independence of Kurdistan, which were stipulated in the Treaty of Sèvres, which was not destined to survive.

While Kurdish sources indicate that the government of Atatürk after the Treaty of Lausanne, did not respect the fact that Turkey was a country of two peoples: the Turkish and the Kurdish, and resorted to the policy of Turkification, and weakening the Kurdish character, it even labelled the Kurds with “Turks of the mountains.” This raised some Kurdish nationalist forces, and the matter was further aggravated by Kemal Atatürk’s declaration to Westernize the Turkish society; Some Kurdish spectrums felt that the bond of religion that linked the Kurds and the Turks were easily abandoned by Atatürk, as he fell into the arms of Europe, embracing Westernization.

At that time, a revolution led by Sheikh Saeed the Kurdish, one of the senior Kurdish clerics, against the Turkish presence; this revolution began in (1925 AD), and it included the eastern provinces of Turkey. Sheikh Saeed was a Sufi, as he was the head of the Caliphs of the Naqshbandi Dervish.

In Ankara, it became clear that the Kurdish rebellion was rapidly spreading in the east of the country and had become a major threat to the Turkish government. Thus, the Turkish government declared a state of emergency; A law was passed to maintain public order, which grants extraordinary authority and powers to the Turkish government, also independence courts were established in the east of the country as well as in Ankara. These courts were given the power to issue death sentences to those it called “rebels.”

It also sent large numbers of Turkish troops to the east of the country; these forces managed to eliminate this revolution, and arrested Sheikh Saeed the Kurdish, after which, the Independence Court in Diyarbakir sentenced him to death, along with 46 of his followers on June 29 (1925 AD), and the sentence was executed the next day.

Given that the Kurdish rebellion had begun at the hands of the Sufi dervishes, and their leader was from the Naqshbandi, Ataturk’s attitudes against the Sufi dervishes evolved, so he closed all their private councils, dissolved their associations, and prohibited their meetings and celebrations.

The American historian Bernard Lewis records the repercussions of this revolution and the law on maintaining order on the whole contemporary history of Turkey, saying: “The Public Order Law – Emergency Law – gave Kemal Atatürk the legal authority to deal, not only with the rebels in the east of the country, but also with political opponents in Istanbul, Ankara, and others. After the Kurdish rebellion, the Progressive Republican Party was banned, and opposition newspapers were strictly censored.

The Egyptian journalist Imad Al-Din Hussein refers to an important phenomenon in the history of the Kurds, saying: “We have no friends but the mountains and the winds.” A saying repeated often by the Kurds, but the majority of their leaders do not comply with it. This saying is considerably true, given the mistaken bets and major disappointments of the Kurdish leaders, the last of which was the Turkish aggression against them in Syria and the fact that America sold them out.

The Turkish betrayal to the Kurds made them believe more in their famous saying, "We have no friends but the mountains and the winds."

- Akml Aldin Ahsan Awghly and others, State Ottoman: History and Civilization, translated by: Salih Saadawi (Istanbul: Research Center for History and Arts, 1999).

- Bernard Lewis: The Emergence of Modern Turkey, translated by: Qasim Abdo Qassem and Samia Muhammad (Cairo: The National Center for Translation, 2006).

- Imad Al-Din Hussein: The Kurds… One Hundred Years of Lost Bets, Al-Shorouk News – Egypt, October 29 (2019).