Bayezid II welcomed them and their residency was legalized by Selim I

Zionists in the Ottoman Empire

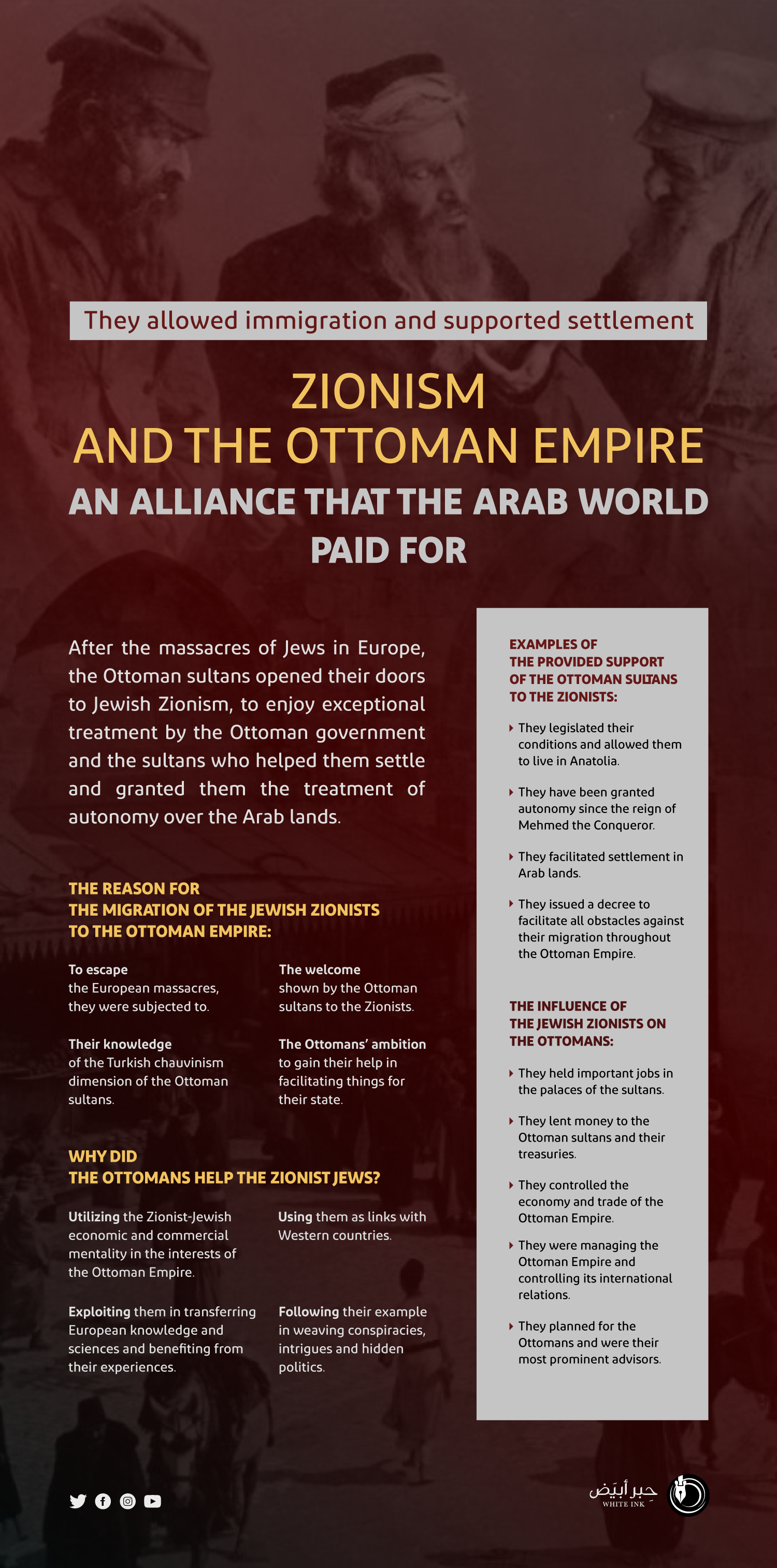

If you think that the Ottoman Empire confronted Zionism everywhere and stood against its settlement schemes to protect the Arab World from this Zionist plague, then you are deluded. They spread their lies in the books without evidence to be provided, Sultans repeatedly narrated such lies to claim fake heroisms to have their memory perpetuated, or slightly enhance their image and erase that dark page in the nation’s history.

But the truth to be narrated, as documented by historical narrations and unanimously agreed by historians, is that the Ottoman Empire was connected to Zionism since its inception; such connection remained until the collapse of the Turks’ authority due to WW I. An extremely interesting story to be narrated is the biography of Jacob Pasha, the personal doctor of Sultan Muhammad the Conqueror. Historical sources conflict with each other regarding the beginning of the Zionist Jacob in the Ottoman court; some of which stated that Jacob, when he began to carry out the duties of his position, was still a Jew, but he converted to Islam later, and was even promoted to the rank of Pasha.

The Ottoman Empire was connected to Zionism from its inception until the end of WW I

There are some historians who provide a different story. They claim that Jacob was a Jew then pretended to be Muslim. Moreover, these sources confirm that he was an agent operating for the Italian Venetians. These sources claim that Jacob was inserted in the Ottoman court in order to help secretly assassinate Muhammad the Conqueror, especially after his expansional conquest in Europe, some confirm this narration, especially, since Muhammad the Conqueror was murdered by poison.

Some protest this narration, based on the fact that Jacob kept working in the Ottoman court, after the death of the Conqueror, during the reign of Bayezid II. Jacob even retained his job. In any case, Jacob’s promotion within the court was mocked and criticized by many, to the extent that some opponents of the Zionist lobby in the Ottoman court, such as Ashiq Pasha Zadeh, satirized Jacob, saying: “The doctor Jacob Pasha became a minister…. Every Jewish and peckish bastard began to interfere in the Sultan’s affairs.” We confirm that what Ashiq Pasha Zadeh said was not anti-Semitic, but only to exhibit the reaction of the current opposing the influence of Jacob Pasha in the Ottoman court.

The Turkish sources state that the settlement of Zionist immigrants from Spain and Portugal, fleeing the massacres carried out by the Catholics against them, commenced during the reign of Bayezid II; he received them and provided living quarters in several regions of the Ottoman Empire for them, especially in Thessaloniki and Edirne.

During the reign of Selim I, the conditions of the Zionists were regulated and the book of Tabu Tahrir for the city of Edirne is considered one of the most important sources in this regard. In 1519, it provided the names of “the people of Spain” and mentioned the names of the head of the Jewish families that were expelled from Spain and settled in Adrianople. This document confirms that the number of these families exceeded forty.

The Turkish Ahmet Aq Kwndz states that in 1993, the Turkish government submitted the previously mentioned document to the European Commission on Human Rights, in addition to the Livadia laws related to the Sanjak of Eğriboz issued during the reign of Selim I, such laws clarified how he allowed the Jews to settle in the Ottoman Empire: “The Jews who come from the West shall pay Kharaj and 25 Oka as a tax.”

While some blame the Ottoman Empire for welcoming Zionists and Jews of Andalusia in the Islamic regions, the contemporary Turks respond to that by saying that this occurred in the context of the heritage of the era of non-Muslims, and the treatment of the Zimmis in Islam, at a time when they neglected the Muslims of Andalusia and let them face their fate.

- Stanford Jk Shaw, Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic (Cairo: Dar Elbasheer, 2015).

- Jaafar Hassan, Eldonmp between Judaism and Islam band, 3rd Ed (Beirut: Al Fajr Foundation, 1988).

- Ahmed Al-Naimi, Jews and the Ottoman Empire (Baghdad: The General House of Cultural Affairs, 1990).

- Ibrahim Allaf, The role of Freemasonry in contemporary Turkish social and political life, Journal of Social Studies, Bayt Alhekma, Baghdad, 3rd and 4th Editions, (1999 – 2000).

- Ahmet Aq Kwndz, The Ottoman Empire for the unknown (Istanbul: Ottoman Researches Foundation, 2008).

- Akml Aldin Ahsan Awghly, State Ottoman history and civilization (Istanbul: Research Center, 1999).

They created a lobby that controlled Sultans

The Golden Age of Zionism in Ottoman Empire

Historical writings are unanimous on the fact that Jews have suffered persecution in Europe more than any other place in the world. This made affiliation to Judaism equivalent to killing or exile during many periods of medieval history in Europe. Such compulsion and persecution state prompted Zionist Jews to constantly search for a political system to involve and accommodate them whatever the concessions in behavioral dealing or material privilege would take.

Arguably, some borders of Ottoman Empire contained areas where Jews lived. The Ottoman Sultans had a very special relationship with Zionists. Therefore, their acceptance to include them in the societal fabric of the Empire, as a whole, has encouraged diaspora to choose Anatolia as a refuge and shelter for them, especially after the positive treatment which they found with Turks against the backdrop of the coordination between Ottoman Empire and Zionists who were very close to the court of Sultans.

In this context, first groups of Jews started to arrive after exiles to which they were subject in Europe. The start was in the Turkish city of Bursa where some groups called “Romaniot Jews” were inhabited as they spoke the Roman language. Then, “Ashkenaz Jews”, the Jews who fled from France, have joined them, as well as “Sephardi Jews” who were exiled from Spain in (1470); in addition to other groups who fled from Eastern Europe such as, Poland and Ukraine.

After the fall of Granada in (1492) mass Jewish migrations multiplied towards Istanbul and nearby cities in the European side and Anatolia, especially after the activation of European inquisitions, and the orders to expel and exile Muslims and Jews who survived burning in furnaces. When Jews arrived in Ottoman lands, they found outwardly full protection and preferential treatment from its Sultans under the slogan of tolerance, freedom of belief, and covenant of protection given to the Zimmis. Notwithstanding, there were inwardly pragmatic considerations as Ottomans deemed that business Zionist mentality a financial base upon which they can rely to domestically and externally support the agendas of the Empire.

Ottomans deemed that Zionism was a business mentality from which they can gain benefit in order to implement internal and external plans of the Turks

With regard to the treatment of Turks with Jews, Turkish journalist, Namik Kemal, said, “After Spaniards had seized Granada, they burned its people who did not change their religion. On the other hand, when we conquered Istanbul we allowed and accorded religious freedom to all sects and religions. As for Jews who were nearly 300 thousand, they were asked to choose either death or conversion to Catholicism. We also know that Ottoman Empire has hosted them too”.

Within the Ottoman Empire, Zionists had a position that was rarely given to other religions and ethnicities. Given their business touch they had over Turkish economy, as well as the generous financial support given to Sublime Porte as some of them even lent The Ottoman Sultans significant amounts to dispose as their private or public interest may require.

The position of Zionists within the economic cycle of Ottoman Empire has contributed to their privileges and senior positions what made other Zimmis, especially Romans and Armenians, bear grudge, and compete with them. They even plotted against them. In spite of such religious and ethnic jostle, Zionists were able to create a strong lobby for them inside the rooms of the Ottoman Empire. They found that their way to the Sultanate court which bestowed the consent of the Ottoman Empire upon them in order for them to live in prosperity and stability what made historians call that era “the Golden Age” of Zionists.

History shows that the distinguished Turkish- Israeli relations were not established out of nowhere; they rather resulted from old foundations and lasted even after the fall of Ottomans and their Empire. Such crowning was reflected in the ceremonies held by world Zionism in (1992) on the occasion of the fifth hundred anniversary of the official welcome that was presented to them by Ottoman Empire in (1492).

- Stanford J. Shaw, The Jews of the Ottoman Empire and the Turkish Republic, transated by: Al- Safsafi Al- Qatouri (Cairo: Dar Al Bashir for Culture and Science, 2015).

- Kamel Sa’fan “Jews: from the Ghetto to the Basements of the Vatican Chapels” (Cairo: Dar Al- Fadilah, n.d.).

- Ahmed Al- Nuaimi, Jews and the Ottoman Empire (Amman: Dar Al- Bashir, 1997).

- Nour Elwan “When Jews fled from Europe to the Ottoman Empire” (Endama Harab Al- Yahod Min Oroba Ela Al- Dawla Al- Othmania), an article published on Noon Post Website through link: https://www.noonpost.com/content/20767

- Ahmed Aq Kunduz and Said Oztok, Uknown Ottoman Empire (Istanbul: Ottoman Researches Foundation, 2008).

The most famous of them is Joseph Nasi and Doctor Yaqoub

The Zionists in the Palaces of the Ottoman Sultans

Since early times, the Zionists found their way into the Ottoman palaces. And within a short period, they managed to control. For further explanation, some Zionists got appointed in remarkable positions. Moreover, during the rule of Sultan Murad II (1421- 1451), they were allowed to possess lands. Therefore, he was called “the great humane person.”

During the reign of Murad II, the chief Zionist physician, Ishak Pasha, who is considered to be one of the first to have a wide influence on the Sultan’s court, emerged. Therefore, Murad II issued a decree exempting this doctor and his family from the tribute, and this was the beginning for many Zionist doctors to hold important positions and jobs in the Ottoman government.

The facts indicate that the Zionists found in the Ottoman Empire a refuge from the persecution, they faced in the European continent. That is, during the reign of Mehmed the Conqueror (1451-1481), the Turks recognized them within the Ottoman religious regime, Millet, which allowed them to live in Istanbul. Besides, a chief rabbi was appointed for them, “Moshe Gabsale”, and the Conqueror granted him wide powers.

Mehmed the Conqueror summoned many Jewish families to live in Istanbul, and during his reign, the Jewish doctor Yaqoub, who obtained the rank of minister, emerged and carried out various diplomatic works for the Ottoman Empire, yet, in return, he was exempted from tribute and taxes. Thus, in the Ottoman Empire, the Zionist Jews lived in such a prosperity that they didn’t encounter in the European continent.

In any case, the Jewish Zionists benefitted, greatly, from the Millet system. It was similar to the citizenship system, that gave them the opportunity to enjoy autonomy. And by the time, Rabbis got to exercise their power in both civil and religious affairs, especially, after the Jews settled in the Ottoman Empire, in late 15th century, hence, ending their diaspora after being expelled from the regions of Andalusia. That is, about 300,000 Jews were expelled, distributed among Portugal, Italy, Morocco and the Ottoman Empire.

During the reign of Bayezid II (1481-1512), a group of Zionist Jewish rabbis submitted to him a request to allow them to immigrate to the Ottoman Empire, and Bayezid agreed, unconditionally, and brought them from Andalusia and had them settled in Ottoman Turkey and its borders, while sent part of them to Chios. Besides, he issued a decree that these people shall live in complete freedom, and even more than that, he ordered the governors of the regions not to refuse their entry, stir up trouble before them, nor to receive them with great hospitality.

The English writer, Bernard Lewis, who specializes in Middle Eastern affairs, says about this: “The Jews were not only allowed to settle in the Ottoman lands, but the Ottomans encouraged and helped them, and in some cases, forced them to settle.” This was confirmed by the French historian André Michal by saying: “the Ottoman Empire provided the homeland for the Jews. That is, it provided them with the guarantee of the organized nation, and the necessary protection under its own control ,and ,hence, all the Jews of the empire became subject to the rabbi Bashi, who resides in Istanbul and is considered an official figure in the country.”

These Zionists happened to hold important positions, among them, for example, was the medical group of Sultan Bayezid II. The immigration of Jews to the Ottoman Empire continued. In the sixteenth century, they immigrated to it from the regions of the European continent. Ottoman and Jewish historical sources refer to the most prosperous periods, that is, the Jews lived in the Ottoman Empire between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, when a number of Jewish Zionists succeeded in holding some high positions and gained influence within the Ottoman court. Istanbul, the Ottoman capital, was the place where some of the fugitive Jews settled, till the population of the ghetto reached by (1590) over twenty thousand.

Western historians agree that the Ottoman Empire was the first to help the Jews settle and to give them autonomy.

Historians, of the memoirs of the Europeans, refer to the influence of the Zionists in the court of the Ottoman Sultan, as well as their remarkable wealth. One of these historians says: “It was not exceptional to find among them (the Jews) some people, each of whom had a fortune of two hundred thousand ducats (golden European currency)”, which is a very large amount at the time.”

Perhaps one of the figures that emerged and had a significant impact on the Ottoman government during the reigns of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520-1566) and his son Selim II (1566-1574) was the Zionist Joseph Nasi, who descends from a Spanish family that immigrated to Istanbul. His influence appeared in the court of Suleiman the Magnificent, due to his knowledge of the conditions and affairs of European politics, of which he was very familiar, hence, his relationship with the legal sultan was strengthened.

During the reign of Selim II, the historical sources indicate that Joseph Nasi’s influence reached its peak during his reign, as he became responsible for the treasury and was based on collecting imports from twelve islands of the archipelago in the Aegean Sea. The annual number of his salary is about sixty thousand ducats. This made him an influential figure in the Jewish community in Istanbul. He was confident and independent within the country of the Ottoman Sultan. He even had his political influence on the Ottoman-French relations, at the time. Yet, his actual influence ended with the death of Sultan Selim II. Still, there are countless number of Zionists in the history of the Ottoman Empire that had an impact on the Ottoman government at all the political, economic and social levels.

- Ahmed Helmy Said, Jewish Activism in the Ottoman Empire (Cairo: Madbouly Library, 2011).

- Ahmad Nouri Al-Nuaimi, The Ottoman Empire and the Jews (Beirut: Dar Al-Bashir, 1997).

- Irma Lvovna Fadeeva, Jews in the Ottoman Empire, Pages in History, translated by: Anwar Muhammad Ibrahim (Cairo: The National Center for Translation, 2020).

- Khalil Enalijk, History of the Ottoman Empire from Origin to Decline, translated by: Muhammad Al-Arnaout (Beirut: Dar Al-Madar Al-Islami, 2002).

- Qais Al-Azzawi, The Ottoman Empire, a new reading of the factors of decadence (Beirut: Arab House of Science, 1994).

- Hamilton Gibb, Islamic Society and the West, translated by: Abdul Majeed Al-Qaisi (Damascus: Dar Al-Mada for Culture and Publishing, 1997).