Anthology of Ancient Religions Philosophies

Persian Origin of Deviant Esoteric Movements in Islam

Esoteric movements are among the most dangerous destructive movements in Islamic history, claiming affiliation therewith, while their hidden true objective was to distract Islamic religion from its genuine purposes, questioning it and its importance. What renders these esoteric movements and their malicious intentions even more dangerous is that most of them have disguised behind an emotional religious slogan.

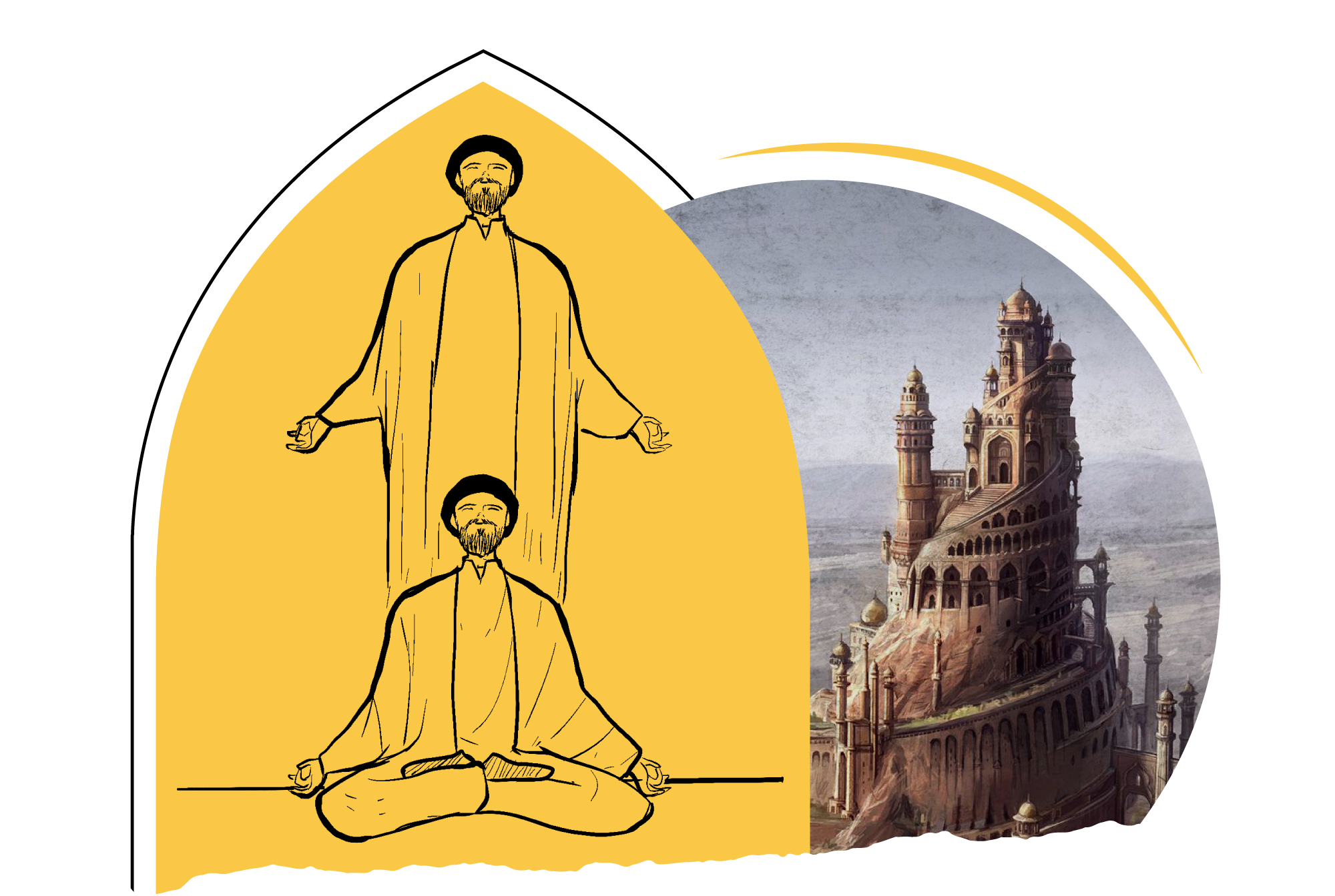

Scholars, almost unanimously, are of the opinion that esotericism was launched by a punch of radicals, which emerged and spread in Islamic world, based on the main call that religious texts have external concepts that the general public is aware of, as well as intrinsic concepts that can only be perceived by the elite whom Allah singled out for matters of faith. Some even went as far as declaring their imams’ divinity. Such radicals were called the esoteric because of their claim that Qur’an and the stories therein have intrinsic meanings much deeper than their extrinsic meanings.

Those movements created the esoteric approach in interpreting Sharia in a manner that ultimately led to Sharia abrogation with a view to popularize their esoteric thought, derived mainly from a mixture of ancient Persian religions and Judaism, consulting Greek philosophy when required. Esoteric movements also denied the various interpretations put forth by the esteemed scholars of Islam. They believed that only the imam is empowered with the right to interpret religious texts. Most esoteric movements believe in the principle of “reincarnation”, i.e., transmigration of souls, whether between man and man or even between man and animal, as supported by their teams.

Among the odd, anomalous teachings was what Maymun al-Qaddah advocated, to whom the Maimuniya is attributed, which is closely related to “Khattabiyyah”, was claiming the prohibition of adopting the extrinsic meanings of Qur’an and Sunnah and rejecting the concept of resurrection in the afterlife.

All scholars responded by rejecting that misguiding and misleading thought of the esoteric movements. Rather, they basically refused to attribute them to the “eccentric / Al-Batin” concept because “Al-Batin” is one of the names of Allah, which linguistically means: the hidden from creatures’ sight and delusions, so He cannot be seen by sight, nor perceived by illusion.

Senior scholars have authored several works in response to the misguided and misleading thought of the esoteric movements. Researchers have unanimously agreed on the role played by Persian extremists in creating the esoteric thought and movement. Abd al-Wahhāb ʻAzzām, one of the pioneers of Persian studies in the Arab world, gives an important political and ethnic explanation behind some Persians creating such movements. He is of the opinion that Persian ultranationalists, despite their conversion to Islam, remained on their hatred of the Arabs and Islam, as was evident in the era of Umayyad state. Then their hopes of controlling the nation were revived with the establishment of the Abbasid state, thanks to the “Persian” Abu Muslim al-Khurasani, whose murder caused a great shock to the Persians, to the extent that they did not believe he was dead. Thereupon, ideas irrelevant to Islam started to emerge, where they believed that Abu Muslim have just “disappeared and shall later come back as a Mahdi”.

They believed in what their Persian culture dictated and wanted to embed it in Islam to serve their popular interests.

Azzām believes that the victory of Aal al-Bayt (family of the Prophet) was merely a pretext and that Abu Muslim and his death led to the emergence of esoteric movements, such as Bābak Khorramdin, where some wanted to demolish the Ka’bah’ in revenge for Abu Muslim’s death. This extended to what the Qarmatians did in the Ka’bah’. ʻAzzām believes that, if anything, this indicates “remnants of religious and sexual fanaticism in the souls of the Persians”.

Persian impact on all mystical movements is clear and obvious. Al-Khatib attributes the historical origin of esotericism to Majūs and Sabeans. Mohamed Al-Khosht also points out that Manichaeism, which is the ancient Persian religion, is one of the philosophical and religious origins of esoteric movements. Also, Al-Hassan e-Sabbah, the founder of the famous Assassins band, which is an esoteric terrorist group, is of Persian origin. He made the call for Hidden Imam in Persia and established a castle for his followers, which is the famous “Alamut” castle. The aforementioned Maymun al-Qaddah was also a Persian. Khorram-Dinān movment, which is attributed to Bābak Khorramdin, was also influenced by Mazdakism, which is one of the ancient Persian religions.

Some Persian esoteric preachers also announced a new dissension when they called for the divinity of the Fatimid Ḥākim bi-Amr Allāh in the year 408 AH. Among the most famous of them was the Persian Hamza ibn ‘Ali al-Zawzani.

The great Iraqi historian Abd al-Aziz al-Douri explains the extremist racist Persian influence in the emergence of esoteric movements; that they, in entirety, seek to pretend to follow Islam, while, in reality, they work to destroy the “Islamic Arab Hegemony”, even destroying Islam from within.

Thus, it can be said that most of the so-called esoteric movements are, in fact, a departure from true Islam. These movements rejected the interpretations agreed upon and called for esoteric interpretation. They were firmly related to the extremist Persian nationalist trend and they were all against Arabs and Islam.

- Mohamed al-Khatib, Esoteric Movements in Islamic World (Amman: (n.p.), 1986).

- Mohamed Al-Yamani, Revealing the Mysteries of Esotericism and Stories of the Qarmatians, their Doctrine and Belief, edited and prefaced by Mhamed al-Khosht (Riyadh: (n.p), (n.d)).

- Abd al-Wahhāb ʻAzzām, Relationships Between Arabs and Persians and their Literature in Pre-Islamic Era and in Islam (Cairo: Hindawi Foundation, 2013).

- Abdel-Aziz Al-Douri, Historical Roots of Shu’ubiyya, 3rd edition (Beirut, (n.p), 1981).