Mazkhor al-Kaabi Revolt (1946)

One of the Severest Ahvazi Reactions that Inflicted Heavy Losses on the Persians

Understanding and assimilating the historical material constitute the first building blocks for building a collective Arab awareness capable of crystallizing a smart strategy that enables realizing Ahvazi Arabs’ dream of liberation from the yoke of Persian colonialism and s rearranging the balance of power in the region favor the Arab Gulf and the entire world.

The method of extortion through the scarecrow of Iran no longer serves either the West or the East. That regime has become an abnormal political situation, internally and externally, which calls for intervention to put an end to Iran as a threat to international peace and security (Article (7) of the UN Charter).

Ahvazi Arabs understood the arrogant nature of the Persians, refused to submit to the fait accompli policy, and declared one uprising after another, although these uprisings or cases of disobedience maintained the nature of reaction rather than initial action.

In this context, Sheikh Mazkhor Al-Kaabi rose up in 1946, yet his revolution was similar to its predecessors; i.e., a reverse reaction to “the massacres that were committed against Saadet Partisi Party (Felicity Party) and extended to all Arabs”. This uprising, which took the coast of the Shatt al-Arab as the headquarters of Sheikh Mazkhor tribe, was able to inflict significant defeats on the Persian garrisons and take revenge to the Arabs “whose blood was stained by the hands of the communists”.

We can deduce from the very first moment that intersection between the revolution of Sheikh Mazkhor Al-Kaabi and “Thawrat al-Ghilman”, where the reaction and victory for one of the Arab symbols were the preludes to the uprising against the Persian occupier, away from the crystallization of a collective revolutionary awareness according to the ground and references that we framed in previous articles. Despite the firmness of mind and pragmatism in any revolutionary act that leads to liberation from external colonialism, yet the manner in which the Persians dealt with the leader of the Felicity Party, Hajj Haddad and his followers, as well as the Persians’ diligence in mutilating the corpses of party members, burning some of them, and beheading the Arabs, created a state of congestion. Thus, the human reaction was aggravated by rejection of the occupation and the Persian ethnic policy, so as to create a state of violent rejection led by Sheikh Mathour Al-Kaabi.

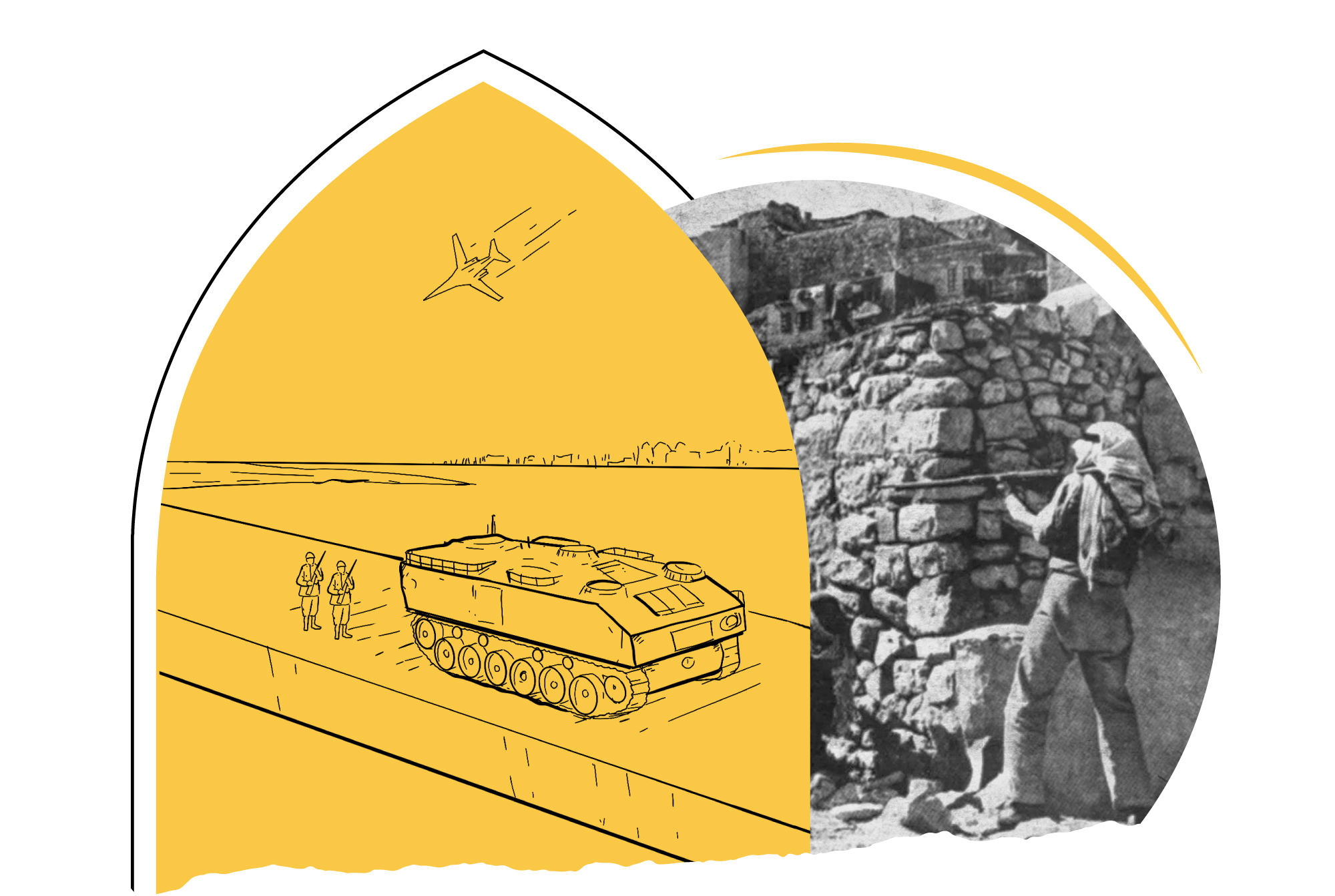

Although the uprising created a state of confusion in the ranks of the Persian occupier, the latter, as was always the case, returned to consolidate its ranks and direct “a strong army, reinforced with modern weapons and armored vehicles, in addition to the use of air force, where Sheikh Mazkhour and his tribe members were bombed, prompting Sheikh Mazkhour to flee to Iraq”.

The method of passive resistance (reactions) cannot create a radical change in an environment that lives on the impact of conflict and between two parties that do not have the same tools and means. Therefore, the balance always tilts in favor of the Persian occupier, who responded to Sheikh Mazkhour’s uprising with several massacres that intended to assassinate the soul of initiative and discourage Ahvazi Arabs against even thinking of revolting against the Persian occupation.

Perhaps the massacres committed by the Persians against the Arabs is derived from the dictionaries of Nicola Machiavelli, who emphasizes the idea that “when it comes to attacking, then attack must be carried out in a way that makes the opponent refrain from even thinking of revenge”. Therefore, the fundamental reason for the failure of the uprising of Sheikh Mazkhor al-Kaabi, and its predecessors, lies in the absence of coordination with the other opposition forces, “although those forces were based, in their movement, on tangible Arab weight that and they had an active role in the struggle against government authorities and Anglo-Iranian oil corporations. Hence, it was easy for the responsible authorities to intervene forcefully to thwart those movements, especially since they (the authorities) were free to act in Ahvaz and were often supported by the British”.

The advanced and heavy military machine is what has always saved the Persian occupier on the land of Ahvaz.

What exacerbated the plight of Ahvazi Arabs was the state of alliance between Iran and Britain, which, in turn, contributed to tightening the screws on the Arabs, thus placing them between the “jaws of pincers”, facilitating the process of suppressing all uprisings that were eager for liberation from Persian colonialism.

Perhaps the changing facts on the field, the presence of a strong Arab depth and the accumulation of political and media momentum around Ahvazi issue, might have changed the facts on the ground, especially since this issue took on geostrategic dimensions. The justice of the issue was combined with the rearrangement of the situation in the region, to the extent that it can be said that the end of Persian colonialism in the Ahvaz region means the end of the state of Iranian control over areas of the Arabian Gulf, thus eliminating one of the most serious threats to Gulf national security.

- Amer Al-Dulaimi, Iranian Occupation of Ahvaz Arab Region, (Amman: Academicians Publishing House, 2020).

- Ali Al-Helou, . Revolutions and Organizations 1914-1966 AD (Najaf: Al-Ghari Modern Press, 1970).

- Ali Al-Sarkhi, History of the National Movement in Ahvaz, (Master’s Thesis, University of Baghdad (2002).

- The Iraqi Ministry of Information, History of Arabistan and the Current Situation in Iran (Baghdad, Ministry of Information Press, 1971).