Persians’ infiltration to the joints of the Islamic State

Umayyads relied on the Arabs and neutralized them, thus the Abbasids secret call was their way through

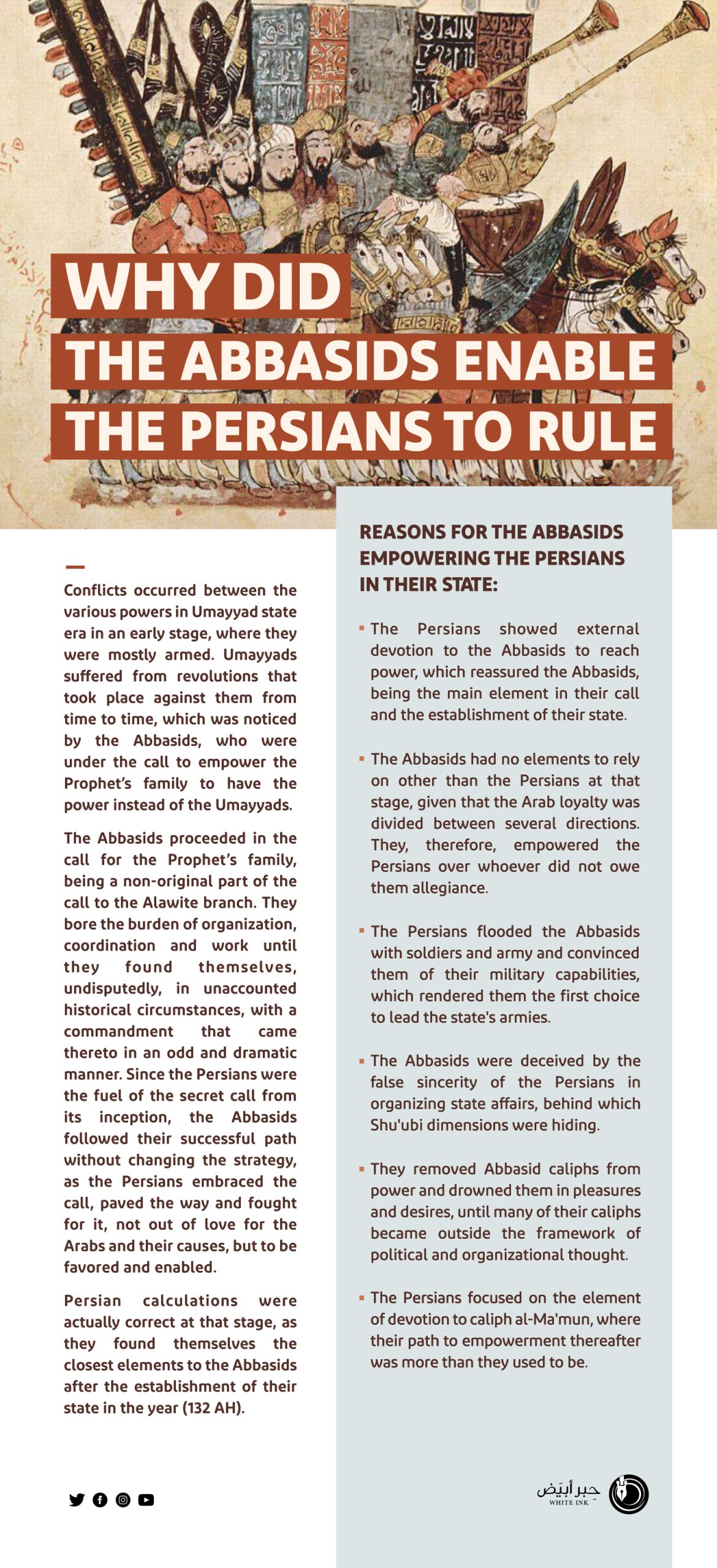

The emergence of the Abbasid state must be read in the framework of the secret call it resorted to and on which it was established, and how it spread rapidly in Persia. Persians became a major component in that call although they did not join the Abbasid call out of conviction, but rather out of their hostility to the Umayyad Arab state. They found in the Abbasids their aspiration to destroy the Arab state that they have always dreamed of eliminating and which they believe have caused the demise of their Sasanian empire and the historical dissolution of their civilization, so as to infiltrate thereafter to the new emerging state based on their alliance with and their support thereto, and overthrew it.

Hence, we must understand why the Arab element was prevalent at the beginning of the Umayyad dynasty and not others, which the Persians accused the Arabs of as the period of formation of the Arab state depended entirely on the Arab element. The state, at that time, was in the beginning of its inception and those peoples who entered Islam did not know the Arabic tongue, nor the method of governance, its mechanisms and details coming from an ancient Arab and Islamic heritage. Arab man was able to contribute to managing the joints of the state and spreading Islam, where no other elements were needed.

Umayyad state depended on the Arabs and a few of non-Arab origin. There is no doubt that Islam came to unify and not to separate, fair among all races. However, Arabs had great tasks in that era, which could not be entrusted to others, foremost of which is the spread of Islam that they knew and inherited, while others were new to Islam. In Persia in particular, there was still a majority over the religion of their Persian fathers and grandfathers.

Arabs are more entitled to the presidency in their country:

Abd al-Wahhab Azzam says in his book Relationships Between Arabs and Persians and their Ethics in Jahiliyyah and Islam: “Arabs were advocates of religion and owners of the state. Because they are the ones who established the state and spread the religion, they see themselves as more worthy of leadership and honor, given their self-esteem and pride in their lineage since the days of Jahiliyyah. The Persians hated them for that, yet they were still overwhelmed by the Islamic conquest and had not yet mastered Islam and the language, nor did they mix with the Arabs in a way that may enable them to compete therewith. The Arabs, on the other hand, had not been weakened, changed and dispersed in the countries yet. Hence, the Persians remained angry for themselves”.

For that reason, Abbasid rebels sought the help of the Persians against the Umayyads, so they helped Al-Mukhtar ibn Abi Ubaid and Abd al-Rahman ibn Al-Ashath, where the army of Al-Mukhtar was of loyalists except for a few. The Arabs reproached him for seeking help from freed slaves and then giving them their share of the spoils. When Abd al-Malik’s messengers said to Ibn al-Ashtar: “Have you come to fight the armies of the Levant with these people?”, he replied: “These are nothing but the sons of the Persian Asawira.”

Ministers of Abbasid Era:

Ministry position in the Abbasid state took a different form compared to that in the Umayyad state. Appointment of ministers was necessary and they were granted broad powers that were not known in the Umayyad state. Hafs ibn Suleiman, known as Abu Salama Al-Khalal (died: 32 AH / 750 AD), is deemed the first to be called a minister in Islam.

Under the Abbasid state, minister position reached a prestigious position. Rather, the minister became a disposer, in place of the caliph, of the affairs of the state .and the people. This is clearly evident in the subsequent role of the Barmakids in Abbasid history, when Yahya ibn Khalid al-Barmaki was granted absolute power, so he became the upper hand in the affairs of peoples and states.

Persian Impact on Abbasid state:

Abd al-Wahhab Azzam also says about the impact of the Persians on the Abbasid policy and in Baghdad, the center of Islam: “The Persians have prevailed over the Arabs among the caliphs since the establishment of the state. The matter culminated with the dispute between Al-Amin and Al-Ma’mun. Al-Ma’mun was in the region of Marw, in the farthest part of Khurasan, like a Persian caliph, where the Persians helped him fighting his brother, who was of great appreciation to Arabs. It was, undoubtedly, a Persian coup under the cover of the Abbasid state, with which the racist Persians were able to hijack the state and turn it into a tool in their hands to achieve their Persian dream of taking revenge on the Arab element and destroying their state that they had always dreamt of destroying. That conflict and bias were documented in Persian poetry and poems were composed for it in praise of Al-Ma’mun. This continued until al-Ma’mun died and the Persians prevailed and remained in control of the caliphs.

The Persians took control of the state and followed the Sasanian Persian culture. Abbasid caliphs started to imitate Persians’ clothes, homes, food and drink, even that Caliph Al-Mansur ordered the Persian cap to be worn. He and those who followed him wore gilded suits in Persian style, even in his image on the dirhams, Caliph Al-Mutawakkil’s was in full Persian costume.

Among the comprehensive words in that regard, Al-Mutawakkil said when he wanted to reform the fiscal year and restore Nowruz to its place in the year, so he brought the jurist to seek his help. The caliph then said: “There is a lot of discussion about this and I shall not go beyond the Persians’ fees” and asked him his opinion on the reform.

Baramkids Power:

As the Persians used to infiltrate the joints of the state, the Barmakids were able to rule the scene during the caliphate of Harun al-Rashid. The caliph took their advice in every matter, until their authority expanded and their status elevated, till they became a subject of poets’ poems.

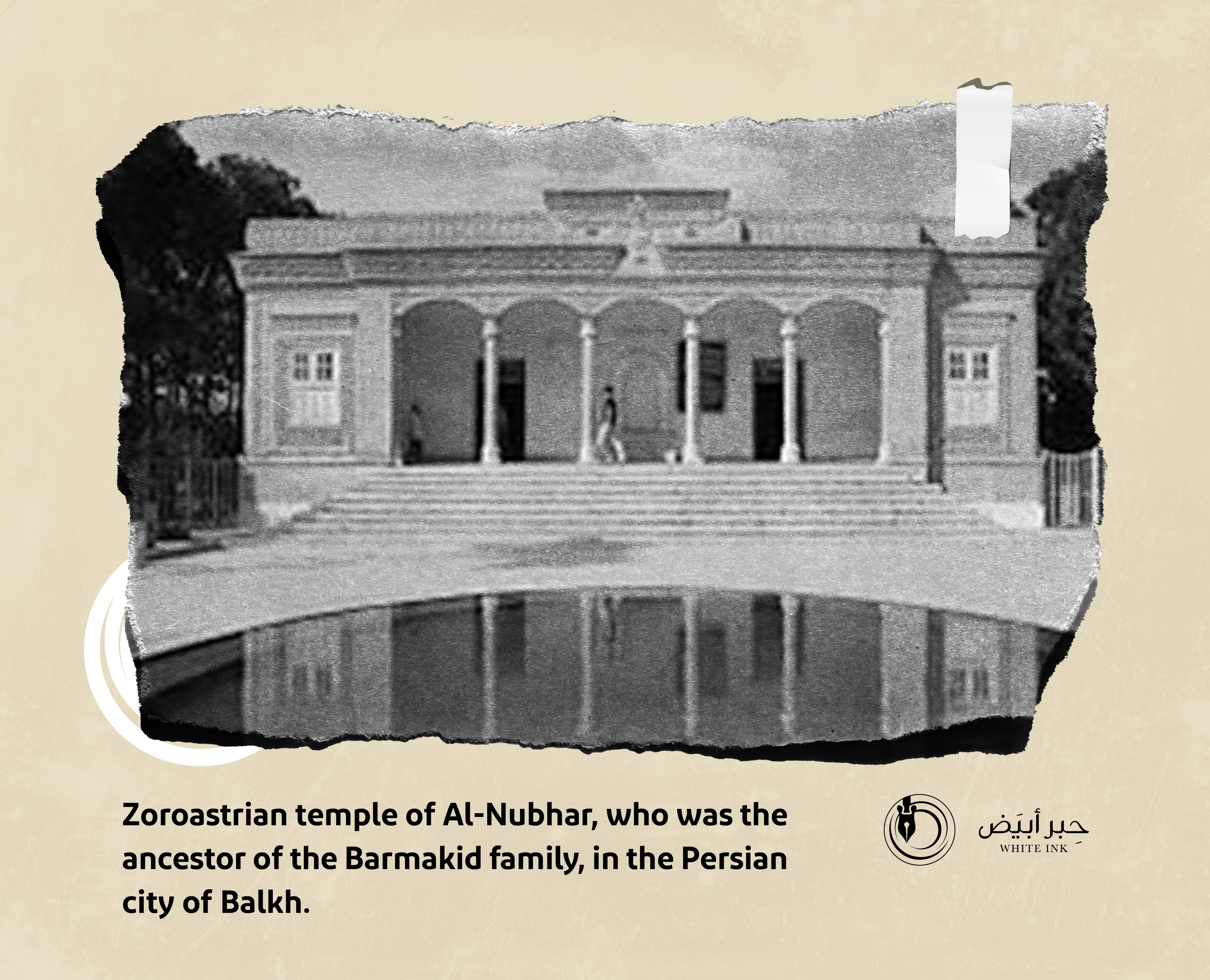

Barmakids are affiliated with Barmak, who is a priest of the House of Fire in the city of Balkh, known as Al-Nubhar, which is a temple of the Zoroastrian religion. That religion was full of complex rituals, magic and secrets, so when they converted to Islam, their chests were not devoid of the effects of that creed. Due to their status and supremacy over the Abbasid authority, they transferred ancient Persians’ books, customs and traditions to the Islamic state. However, their domination exceeded that to controlling all funds of the state. This went to the extent that if caliph Harun al-Rashid wanted to decide on any matter, he had to consult with them thereon. The first figure that emerged from among them was Khalid al-Barmaki. Their status elevated during the era of al-Rashid at the hands of Yahya ibn Khaled.

Grandfather Khaled Al-Baramki is considered the first Baramkif to contact the Abbasids during the Abbasid call. He played a prominent role in this call and the developments it went through until the Abbasid state was established in the year (132 AH). As a result, Khalid al-Barmaki assumed the first office in-charge of taxpayers and soldiers, and he was with al-Saffah in the position of a minister, especially after Abu Salama al-Khalal was killed. He worked as a minister and, during the era of Al-Mansur, Khalid assumed one of the key positions in the Abbasid state. He was entrusted with the ministry at the outset of Al-Manusr’s era, then he was entrusted with the state of Persia, followed by Al-Ray in Tabaristan and Dunbound. He also worked as an advisor to the caliph Abu Jaafar al-Mansur, where such position was of great importance to the Al-Barmaki in his position, as he was involved in decision-making and in drawing up the policy that al-Mansur was pursuing.

The Abbasids empowered the Persians because their call emerged among them and with their support, thus they fell into the trap of their Shu'ubiyya.

As for the Barmakids disaster, it took place in their own hands rater than by others due to their domination and seizure of the state, not to mention usurping all Muslim money, to the extent that when Al-Rashid asked for a small sum of money, they refused. So they overpowered and shared his authority. He was helpless in managing the affairs of his state. Al-Barmaki appointed twenty-five of his children in the caliphate house to be his eyes therein and prevent others from reaching the state’s affairs!

- Ahmed Amin, Harun al-Rashid (Cairo: Hindawi Foundation, 2014).

- Amira Bitar, History of the Abbasid Era, 4th edition (Damascus: Damascus University, 1997).

- Sayyid Salem, First Abbasid Era (Alexandria: University Youth Foundation, 1993).

- Abdel Wahhab Azzam, Relationships Between Arabs and Persians and their Literature in Pre-Islamic and Islam (Cairo: Hindawi Foundation, 2013).

- Muhammad Barang, Baramkids in the Shadows of the Caliphs (Cairo: Dar Al-Maarif, n.d.)

- Mohammad Al-Khudari, Lectures on the History of Islamic Nations: The Abbasid State, edited by Mohammad Al-Othmani (Beirut: Dar Al-Qalam, 1986).

- Nabila Hassan, History of the Abbasid State (Alexandria: Dar Al-Maarefa Al-Jamieya, 1993).

Baramkids..

Offspring of Saden the Magi who incited the people of Balkh to break their covenant with the Muslims

The history of the Barmakids’ ancestors was linked to their religious activity in the city of “Balkh”, which is one of the most famous cities of Persian Khorasan that was, at that time, a sacred city that neighboring peoples visited annually to offer sacrifices. Barmakids’ ancestors were the custodian of the known as “Nubhar” temple, where their grandfather, Barmak al-Majusi, was the custodian of the Temple of Fire. Barmak and his sons were famous for their custodianship, which gave them great value and appreciation.

The Barmakids retained religion until the end of the Umayyad dynasty in 90 AH / 708 AC. Their grandfather, Barmak, was one of the instigators in Balkh to break the peace with the Muslims. Information is ambiguous about the life of Khaled al-Barmaki or even his Islamic upbringing. Some historians believe that he grew up on the Magi religion, the religion of his ancestors, and that his political activity began with the Abbasid call. Then, with the passage of time and the establishment of the Abbasid state, as Al-Isfahani says about the increasing influence of the Barmakids and their control over matters in the state: “That in the state of al-Rashid, there was another state ruled by the Baramkids”. Yahya ibn Khalid al-Barmaki was the owner of the supreme word in the affairs of the state. He has the ministry of delegation and all offices. Yahya was granted serious privileges. He was the first empowered minister who was exclusively in-charge of writing to the governors, where such correspondences were issued only by the caliph himself in the past. Yahya had seized all political, administrative and economic powers.

Khaled took over and advanced in the Abbasid state and took over the ministry for Abu Abbas after Abu Salama Hafs Al-Khalal. Al-Masoudi said about him in his Mourouj Al-Thahab: “None of his sons reached the level of Khaled ibn Barmak in his generosity, opinion, strength, knowledge and all his trait. Yahia was not in his wisdom and abundance of mind, Al-Fadl ibn Yahya was not in his generosity and integrity, Jaafar ibn Yahya was not in his written and oral eloquence, Mohammad ibn Yahya was not in his agility and determination and nor Musa ibn Yahya was not in his courage and valor”.

Yahya Al-Barmaki first emerged during the period when his father Khaled assumed positions in the reign of Abbasid caliph Abu Jaafar Al-Mansur and during the short reign of caliph Al-Hadi. Yahya Al-Barmaki replaced his father in the leadership of the Barmakids. During that important historical period, Harun Al-Rashid, the crown prince and brother of the caliph, was closely associated to Yahia, who was in charge of writing for Al-Rashid. Historical sources also refer to the role played by Yahya al-Barmaki in supporting Harun al-Rashid as the person entitled to assume the prince position. When Caliph al-Hadi wanted to give his young son that mandate, instead of his brother Al-Rashid, Yahya refused and said to Al-Hadi: “Do you think that the people will hand over the caliphate to Jaafar while he is still a child and will accept his as their caliph?”

The increasing influence of the Barmakids during the reign of Harun al-Rashid impacted the situation within the Abbasid court to the extent that some of the caliph’s entourage were fed up with the Barmakids’ evil. Conflict raged between the Barmakids and their opponents until the latter were able to convince the caliph that the Barmakids are an evil spreading in the state and that he must be rid of them. The Barmakids had previously poisoned Musa ibn Jaafar al-Kazim after a trip to Harun al-Rashid, when they accused Musa that he wanted to overthrow him. Harun wept over his cousin and knew the Barmakids’ plot. He was smart and aware of the Barmakids’ influence in the state. He realized that getting rid of them was not an easy matter, yet he decided to arrest all the Barmakids, confiscate their money and property, displace some of them and kill some others, while many of them were prisoned. This, the legend of the Barmakids ended and their authority within the Abbasid state ended within few hours. Al-Rashif battle against them was called as the Barmakids’ Disaster”.

After Harun al-Rashid, the Persians almost divided the Abbasid state between eastern and western states.

Barmakids’ disaster is caused by the hidden struggle waged by the Persians against the Arabs, which continued after that during the reign of Al-Amin and Al-Ma’mun. That conflict appeared clearly during the era of Al-Rashid when he entrusted his son Al-Amin with the mandate of the Covenant after him in the year (175 AH) under Arab influence, represented in his wife Zubaydah bint Jaafar and his chamberlain Al-Fadl ibn Al-Rabea. Al-Amin was then five years old, indicating that the intent was only to guarantee succession to the Arabs. The Persian side, headed by the Barmakids, was not satisfied with that situation, so they tried with Al-Rashid until they convinced him to entrust his son Al-Ma’mun with the mandate of the Covenant after Al-Amin in the year (182 AH), provided that Al-Ma’mun shall assume the mandate of the East after the death of his father. In other words, the succession of Al-Amin after the death of his father on the east shall be only a camouflage. It is known that Al-Ma’mun was from a Persian mother and that is why he was supported by the Barmakids. In the year (186 A.H.), Al-Rashid performed Hajj with his two sons, Al-Amin and Al-Ma’mun. In the Sacred House of Allah, he took their vows to be loyal to each other and that Al-Amin shall leave to Al-Ma’mun the mandate on the east states, with all their frontiers, villages, soldiers, taxes, money houses, alms, tithes and mail. Al-Rashid recorded those covenants are in the form of decrees and hanged them in the Kaaba to increase their sanctity and confirm their implementation. He also circulated that meaning, in writing, to all states. Thus, the Arabs guaranteed the succession to a person with Arab lineage, while the non-Arabs, under the leadership of the Barmakids, guaranteed the east to a man who they were his maternal uncles.

- Qouider Bashar, The Role of the Baramkids in the History of the Abbasid State (Algeria: Institute of History, 1985 AD).

- Abdel Moneim Al-Hamiry, Al-Rawd Al-Matar fi Akhbar Al-Aqtar, edited by Ihsan Abbas (Beirut: Lebanon Library, 1975).

- Ali Al-Amr, Impact of the Political Persians in the First Abbasid Era (Cairo: Al-Degwi Press, 1979).

- Mohammad al-Jahshiari, Book of Ministers and Writers, edited by Mustafa al-Sakka et al (Cairo: n.p. 1938).

- Yaqut Al-Hamawi, Dictionary of the States, (Beirut: Dar SAD, 1975).

Soul Brotherhood…

Did not intercede Arab’s “Harun” to Persian’s “Jafar”

Any reader of Abbasid history stops at the disaster of the Persian Barmakids, which occurred during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Al-Rashid was aware of matters of politics and governance with his pivotal personality, which some history books wronged by linking his reign to sultan’s glory and the life of palaces and maidservants, disregarding the civilized aspects that occurred during his reign.

Barmakids influence began to expand with Abu Jaafar “Al-Mansur” solely seizing the Abbasid rule, upon which he began empowering them in the joints of the state until they were able to rule directly. Rather, “The era of those ministers was the beginning of a golden era of slavery for the Abbasid caliphs, as they enjoyed only the shadow of the throne except and scepter and crown of the power, till until Harun Al-Rashid took over and put an end to the wide authority of the ministers”.

The importance of studying the issue of the Baramkids is in its being a basic introduction to monitoring the seriousness of all political organizations that strive to control the joints of the state and direct the political decision making in a direction that serves the agendas of empowerment, especially among those with different ideologies. Barmakids’ disaster is an important sign for the use of elements that owe allegiance first and foremost to the state, away from intolerance to a race, tribe or sect.

Above all, honesty entails acknowledging that the Barmakids, at the beginning of their reign in the ministry, managed well and mastered the expression. They were able to obtain the approval of the Abbasid rulers since Khaled Al-Barmaki penetrated the joints of the Abbasid state, given his ability to patience, flattery and good management. Yahya Al-Barmaki followed his path and was able to reach a higher rank than that reached by his father Khaled, which allowed him to plot and conspire until he was able, with the support of Khayzaran, Harun’s mother, to bring Harun to power as the legitimate crown prince.

Jaafar ibn Yahya Al-Barmaki did not deviate from the path of the Barmakids, which enabled him to become the closest person to Harun Al-Rashid. He combined “eloquence of written and oral words, morals and humility. That is why he was of great standing and rank with al-Rashid; in a position that no Arab or non-Arab person could share therewith”.

However, examining the personality of Jaafar al-Barmaki, we are facing a complex and contradictory situation. Almost all writings unanimously mention his love for Harun al-Rashid and his dedication to his service. However, those same writings differ about the reasons for Al-Rashid’s discontent with him although he was his companion and brother of his soul. Some writing expaling that mainly by the struggle for power, while others deal with the complex relationship that linked Jaafar with Al-Abbasa, sister of Al-Rashid. These are the details about which the narrators of history differed; e.g., Al-Tabari and Ibn Khaldun.

In this regard, there is difficulty in monitoring the estrangement between the Barmakids and Harun al-Rashid. “Therefore, despite the enormity of the Barmakids’ disaster, opinions have greatly varied about its causes till it is not possible for any researcher to actually depict what was the real cause”.

Regardless the dispute over the direct causes of the Barmakids’ disaster, Jaafar in particular, intersections unanimously agree that the Barmakids felt that they the state owes them a lot of favor and that building it would not have been possible without them, especially since they combined the authority of the owner of the state (Yahya al-Barmaki) and the backbone of the army that was monopolized by Al-Fadl ibn Yahya, Harun’s milk brother. If we accept that Barmakids’ ambition reached the level of thinking of subjugating the head of the political authority, yet aafar ibn Yahya’s coup against his friend, companion and successor cannot be explained only by self-identification with the Barmakids’ aspirations, but also by the complications of Jaafar’s desire to marry the sister of the caliph, Al-Abbasa”.

We might believe that Jaafar Al-Barmaki’s fanaticism towards his family and Harun Al-Rashid’s refusal to mix the blood of the Arab caliphs with the blood of the Persian Barmakids prompted the first to plan to get rid of this existential obstacle represented by the caliph. “His (Jaafar’s) ambitions were mixed with amorous considerations” and “he tried to overthrow the throne of Caliph Harun in order to seize it”.

In sum, Jaafar considered the Barmakids’ opinion in terms of their favor made to the Abbasid state and the empowerment of Harun al-Rashid against the will of his brother al-Hadi, which is the adventure resulted in cutting Jaafar’s head and mutilating his body, as historians agreed that Harun “sent his corpse and his head to Baghdad, the city of peace, and ordered his head to be hanged on a bridge and the body to be cut into two pieces”.

The complicated relationship with Al-Abbasa prompted "Al-Barmaki" to attempt a coup against "Al-Rashid".

In conclusion, we find that the Persian ideological and ethnic dimension is inconsistent with the case of Al-Rasheed and Jaafar; as Persian racism triumphed over the meanings of brotherhood between an Arab and a Persian and it was stronger than sincere psychological serenity. If Al-Rashid has not discovered Jaafar’s betrayal, he would not have ordered to kill him, his soulmate, before he arrested his brother Al-Fadl and cause the Barmakids’ disaster.

These historical accumulations have produced for us an extended political reality in Persian’s dealings with the Arabs; their lack of purity and their political intrigue favor the victory for their racism. This explains the facts of today’s environment in the Iranian plot against the Arabs, as rooted in historical contexts.

- Amira Bitar, History of the Abbasid Era, 4th edition (Damascus: Damascus University, 1997).

- Sayyid Salem, First Abbasid Era (Alexandria: University Youth Foundation, 1993).

- Ragai Attia, Blood on the Wall of Power (Cairo: Dar Al Shorouk, 2017).

- Muhammad Barang, Baramkids in the Shadows of the Caliphs (Cairo: Dar Al-Maarif, n.d).

- Muhammad Al-Khudari, Lectures on the History of Islamic Nations: The Abbasid State, edited by Muhammad Al-Othmani (Beirut: Dar Al-Qalam, 1986).

- Nabila Hassan, History of the Abbasid State (Alexandria: Dar Al-Maaref Al-Jami’eya, 1993).