The Russian Calamity in Servicing the Dictatorship of the Ottoman Sultan

Jouka: Abdul Hamid was

“like a scared kid that his back scourged with a thick truncheon”

Russian-Ottoman relations were marked by an intense rivalry between the two empires; which sometimes were taking a religious dimension and, at other times, colonial and economic dimensions. When the religious conflict centered mainly on the privilege that was associated with the monopoly of religious reference in the region. Especially after the fall of Constantinople by the Ottomans, that was a historic opportunity for Tsarist Russia, which considered itself as the rightful heir to the Byzantine Empire.

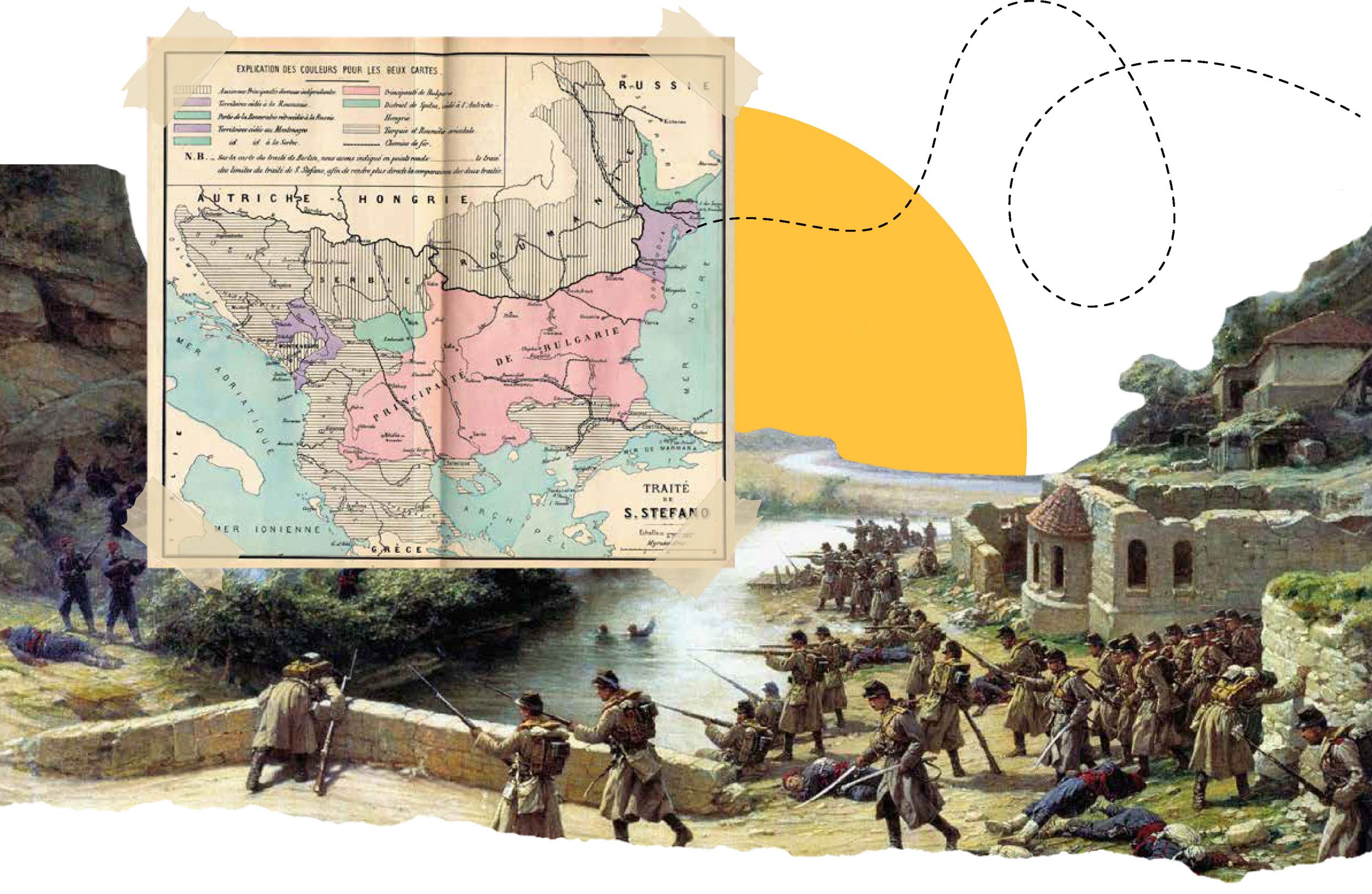

Strategically, Russia was unable to access the warm waters of the Mediterranean, which led it to try to coerce the Ottomans to allow it to use the waterways for commercial purposes and other war purposes. That was a scramble, which took severe forms, particularly in the 19th century, when the Crimean Wars broke out (1853-1856 AD). That war ended with the Paris Conference, which grants great privileges to the Ottomans before the outbreak of the Balkan War (1877-1878 AD). The later war ended in a humiliating defeat for the Ottomans. When they were forced to sign the Treaty of San Stefano. Then some countries intervened to save the face of the Sultanate and called for Berlin Conference that could be considered the practical beginning for the fall of the Ottoman State, and opening the file of the so-called Eastern question.

The term “Eastern Question” is used to refer to all problems that were associated with the internal collapse of the Ottoman State and the revolutions of the peoples that were ruled by it. Finally, the term refers to the interwoven and conflicting interests of the European states in the Ottoman Empire as well as their intervention in the process of the Ottoman collapse.

The purpose of studying the relationship of Sultan Abdul Hamid II with Russia is not related to re-ruminate the historical facts that are filling books and literature, which monitored the relationship between the Ottoman State and the Tsarist Russia. But rather, it is by attempting to answer the methodological problematic that is deemed the center of gravity for the scientific article. This problematic, we believe, remains related to the answer to the following question: How did the military defeat before Russia contributed to strengthening the political influence of Sultan Abdul Hamid II? And how did the latter take advantage of post-war circumstances to successfully transform the government system of Sultanate from a parliamentary system to a dictatorial one that led some to describe the Sultan as a “tyrant”?

In this context, the internal political situation that followed the assumption of Abdel Hamid II for the mandate of the throne was quite critical. As the form of eliminating and killing or suicide of the Sultan Abdul Aziz remained and never left his imagination. Especially that some, of those whose hands were bloodied, were still holding important positions as well as moving entirely free in the political center. That made him suspect this junta, as he kept saying that rebels and revolutionaries will continue to be spoilers in every time and place. Abdul Hamid was waiting for the right opportunity to eliminate those who were stalking the seat of Sultanate.

On the other hand, the Russians considered that Constantinople as a religious symbol and a strategic importance for its control of the waterways of Bosphorus and Dardanelles that leading to the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. Thus, the control of these waterways means ensuring the freedom of transit for merchant vessels and warships. Particularly, since the economic weight shifted to the Russian seaport of Odessa that was bordering the Black Sea.

The Russians practiced their tutelage of Istanbul, as they considered that as a religious symbol for them during the era of Abdul Hamid II.

The Balkan Question

The defeat of the Ottoman State against Russia and the Balkan countries formed a historic opportunity for these countries to demand their complete independence from the Ottoman rule. Where a set of subjective and objective requirements were available to realize the dream of their independence. However, the religious element was presenting in the calls for independence, most writings confirm that the religious motivation was a peripheral compare to the widening gap of social inequalities due to the negative social policies of the Ottoman State. In addition to the rise of national trends without eclipsing the intervention of some of European powers that felt themselves directly or indirectly concerned with the Eastern question.

It can be argued that the Ottoman policy in the Balkans region, unlike that some people are promoting, affected not only Christians but also Muslims there. It was even argued that Muslims were more affected by the Ottoman policies and reforms that were limited to Christians but did not include the Muslims, such as the elimination of certain taxes and exemptions from military service, among others. In addition to the preferential intervention of foreign consuls for the benefit of Christians. Despite this discrimination, Balkan society suffered from a serious class policy. As the Social inequalities were not between Muslims and Dhimmis, yet they were between a ruling class and a governed one. In each class, one could find people of both categories.

The class conflict that contributed to the process of mobilization and crowding against the Ottoman State would be exploited by Russia, where Marxist ideas that crystallized thereafter and began to be active at that time to declare that the class conflict is one of the “most important tools of the revolution” in the words of Leon Trotsky.

In this respect, Tsarist Russia took advantage of the policy of arbitrariness, authoritarianism, and the taxation and collection system, which was imposed by the Ottomans on the inhabitants of the region – to strengthen the national feeling of the peoples of the Balkans. Further, it prompted them to revolt against the Ottoman rule. Where they took advantage of the internal situation of the Sultanate, which was living in the impact of an internal political crisis that was threatening its continued existence and leading to the demise of the Ottoman Family Sultan.

Abdul Hamid II was avoiding any direct confrontation with Russia

Abdul Hamid II tried to avoid upsetting Russia and attempted to befriend it in a manner that is inappropriate to the history and weight of the Ottoman State. As Suleiman Jouka Bash describes the behavior of Abdul Hamid II as: “a scared kid that his back scourged with a thick truncheon”. This feeling was recounted by the princess Aisha Osman Oglu, the daughter of the Sultan, in her diary, as she said: “He has not missed any opportunity to strengthen the ties of cordiality and friendship with the Russian Tsar in order to protect the Ottoman State from the threatening dangers that could cause by Russia. Additionally, that our geographical conditions impose this on us and make it as an inescapable and imperative duty”.

Abdul Hamid II demonstrated a great flexibility in his dealing with the Russian Tsar. Further, he showed a readiness to cede some of the territories that were under the Ottoman Sultanate. Nevertheless, he was manipulating to continue controlling the waterways that were as the most paramount political target to Russia for accessing the warm waters of the Mediterranean. In this regard, the Ottoman Sultan stated that: “For Turkey, the Straits are a matter of life. So we must conserve and protect them at all costs”.

He avoided disturbing Moscow, even in humility.

Abdul Hamid II and the confrontation with Russia:

The Russian-Ottoman War, or what is historically known as the Balkan War, although it led to the defeat of the soldiers of Sultanate and to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire delusion. However, there are evidences which indicate that the most beneficiary of this defeat was the Sultan Abdul Hamid himself. When he exploited the “calamity” to concentrate all powers in his hand. Moreover, he dissolved the Ottoman parliament and disrupted the democratic mechanism of governance. As he issued a decree, which was read by the Prime Minister Ahmed Rafiq Pasha, to suspend the parliament. It was recounted that the Sultan said after the decision of suspension: “It turned out to me that I was wrong, when I attempted to serve my nation through following the course of my Father, Sultan Abdul Majid, and establishing democratic institutions. Now; however, I would follow the course of my grandfather, Sultan Mahmoud, because, at this moment, I have come to believe that the course of power is the only way through which I could serve the nation that Allah has entrusted me to lead and preserve it “.

Similarly, it can be said that Sultan Abdul Hamid II, in common with the new Ottomans, took advantage of the relapse in front of Russia to transform the system of government from parliamentary to totalitarian, as well as to concentrate all powers in his hand. As he attempted to rule the areas under the Ottoman Sultanate with a strong hand, which is the dictatorial policy of which the Arabs would suffer the lion’s share.

1. Abdul Raouf Snow, “Russian-Ottoman Relations: The Policy of Impulse Towards Warm Water, Journal of Arab and World History, No. 73-74 of 1984, p. 48.

2. Abdul Raouf Snow, Ibid, No. 79-80 of 1985, p. 5.

3. Suleiman Jouka Bash “Sultan Abdul Hamid II, his Character and his Policy”, The National Center for Translation, Istanbul 1995, p. 297.

4. Ibid, p. 298.

5. Diary of Aisha Osman Oglu “My Father, Sultan Abdul Hamid II”, Dar Al-Bashir for Publishing and Distribution, Jeddah 2007, p. 49.

6. Suleiman Jouka Bash, Ibid, p. 300.

7. Orkhan Muhammad Ali “Sultan Abdul Hamid II: His life and the events of his reign”, Istanbul 2008, p.95.