They formed ministries and controlled over councils and bodies

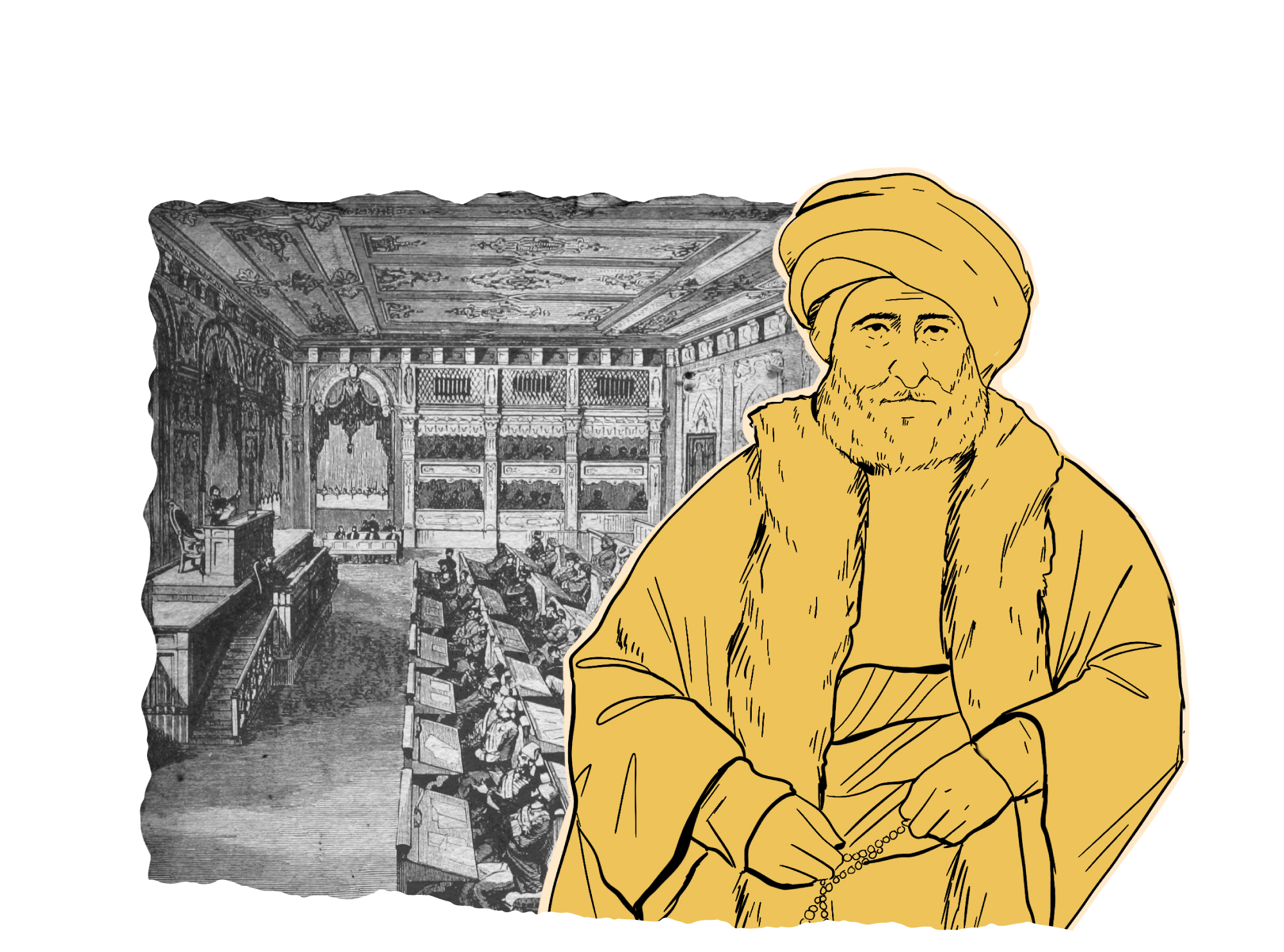

The Zionist administration in the Ottoman Empire

Historical sources confirmed that the Zionists had always been in the bodies of the Ottoman Empire at different stages, and the Turks allowed them to take power from the fifteenth century AD until the eighteenth century. They were doctors and advisors close to the Ottoman sultans, and they were close to the statesmen like the Grand Viziers and the influential people in the Ottoman administration. For example, in the middle of the eighteenth-century AD, Tunisia was under the Ottoman occupation, and the Jews were assigned to collect levies and taxes for a long time. Rather, there are lists of the names of those assigned to such categories, businesses, goods and various industries, in addition to their assignment to customs in some states of the Ottoman Empire. This is what was observed in Iraq, the Levant and Al-Ahsa. Therefore, the employment of the Jewish Zionists in the financial management positions of the Ottomans was an old strategy.

In fact, decrees such as “Kalkhana hatt-ı hümâyûn or Tanzimat Fermanı” (1839) and “Humayuni Line Repairs” (1856), directly affected the conditions of the dhimmis in the Ottoman Empire, including the Jewish Zionists, who were allowed by those decrees and reforms to take over government jobs. For example, there were about eight Zionists in the translation room at the Sublime Porte, and about seventeen Zionists in the external editing. There were about eight Zionists in the counseling room of the Sublime Porte. We can say that: The Zionists assumed important governmental positions during the period from (1850) to (1908), especially in the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Most of them were educated in European schools, and most of the Zionist employees spoke several languages, such as German, Spanish and French.

Jews dominated important positions in the state and took over the collection of taxes in several Arab states by order of the Ottomans.

The Turkish historian Oztuna says: “The reforms of 1856 AD removed this difference as well (a condition that the employee in the state must be a Muslim) and made all official state jobs available to non-Muslims in the last 66 years of the empire except for scholarly jobs (religious scholars). The sects were appointed to all jobs except for the supreme leadership, so they became ministers of foreign affairs and ministers of finance, and many of them were given the highest ranks as ministers and pashas. They became ambassadors and governors of the provinces”.

Some Jewish Zionists reached such high positions that one of the Ottoman governments included three Zionist ministers: Bsariya Effendi as Minister of Works, Nissim Mazliah as Minister of Trade and Agriculture, and Javed Bey of the Donme Jews as Minister of Finance in the Ottoman government in 1913.

The Jewish Zionists also had the right to be represented in the Ottoman Parliament Since 1876. During the reign of Abdul Hamid II, the members of the body of notables amounted to about 38 members, eleven of whom were non-Muslims, including Christians and Jews. The first council consisted of about 69 Muslim members and 46 non-Muslim members. The Zionists participated at the level of functional classes from the highest to the lowest in functional terms.

The list of Zionists who held various positions in the Ottoman Empire included -but not limited- to: Nassim Jabra, who was the director of the Thessaly Telegraph Office. Jack Shalem, who was a Pharmacist officer in the Humayun Navy. Abraham de Camondo, who was a member of the board of directors of a neighborhood in Istanbul. Abraham Khatam Effendi, who was a member of the Court of Justice. Isaac Dutton who was a member of the Commercial Court in Izmir. This is an aspect of the invasion of the Jewish Zionists into the administrative bodies of the Ottoman Empire.

- Ahmed Helmy Said, Jewish Activism in the Ottoman Empire (Cairo: Madbouly Library, 2011).

- Ahmad Nouri Al-Nuaimi, The Ottoman Empire and the Jews (Beirut: Dar Al-Basheer, 1997).

- Irma Lvovna Fadeeva, Jews in the Ottoman Empire, Pages in History, translated by: Anwar Muhammad Ibrahim (Cairo: The National Center for Translation, 2020).

- Reda Ibn Rajab, The Jews of the Court and the Jews of Money in Ottoman Tunisia (Beirut: Dar Al-Madar Al-Islami, 2010).

- Abdullah Nasser Al-Subai’i, Governance and Administration in Al-Ahsa, Al-Qatif and Qatar during the Second Ottoman Rule 1288-1331 AH / 1871-1913 AD, a Documentary Study (Riyadh: Al-Jumah Electronic Printing Press, 1999).

- Yilmaz Oztuna, History of the Ottoman Empire, translated by: Adnan Mahmud Salman (Istanbul: Publications of Faisal Finance Corporation, 1990).